Deze masterproef onderzoekt de typologie van de ‘onzichtbare reuzen’ in Gent: appartementsgebouwen die in de jaren ’60 en ’70, aangevoerd door grote ontwikkelaars zoals Amelinckx en Etrimo, Belgische grootsteden overspoelden en tot op heden grotendeels buiten de architecturale aandacht zijn gebleven. De masterproef focust expliciet op de brede productie van dit soort ontwikkelingen, en niet alleen op het werk van enkele grote spelers.

Er wordt vertrokken van het bestaande patrimonium en gekeken naar hoe deze ontwerpen, die destijds vanuit een hele specifieke, rationele insteek zijn ontstaan, vandaag bewoond, beleefd en gewaardeerd worden. Deze masterproef heeft niet als doel om een gedetailleerde historische reconstructie te maken of om een uitgewerkte toekomstvisie te formuleren, maar is een poging tot herlezing. Via observaties, gesprekken met bewoners en visuele representaties wordt gezocht naar een nieuwe benadering van deze typologie.

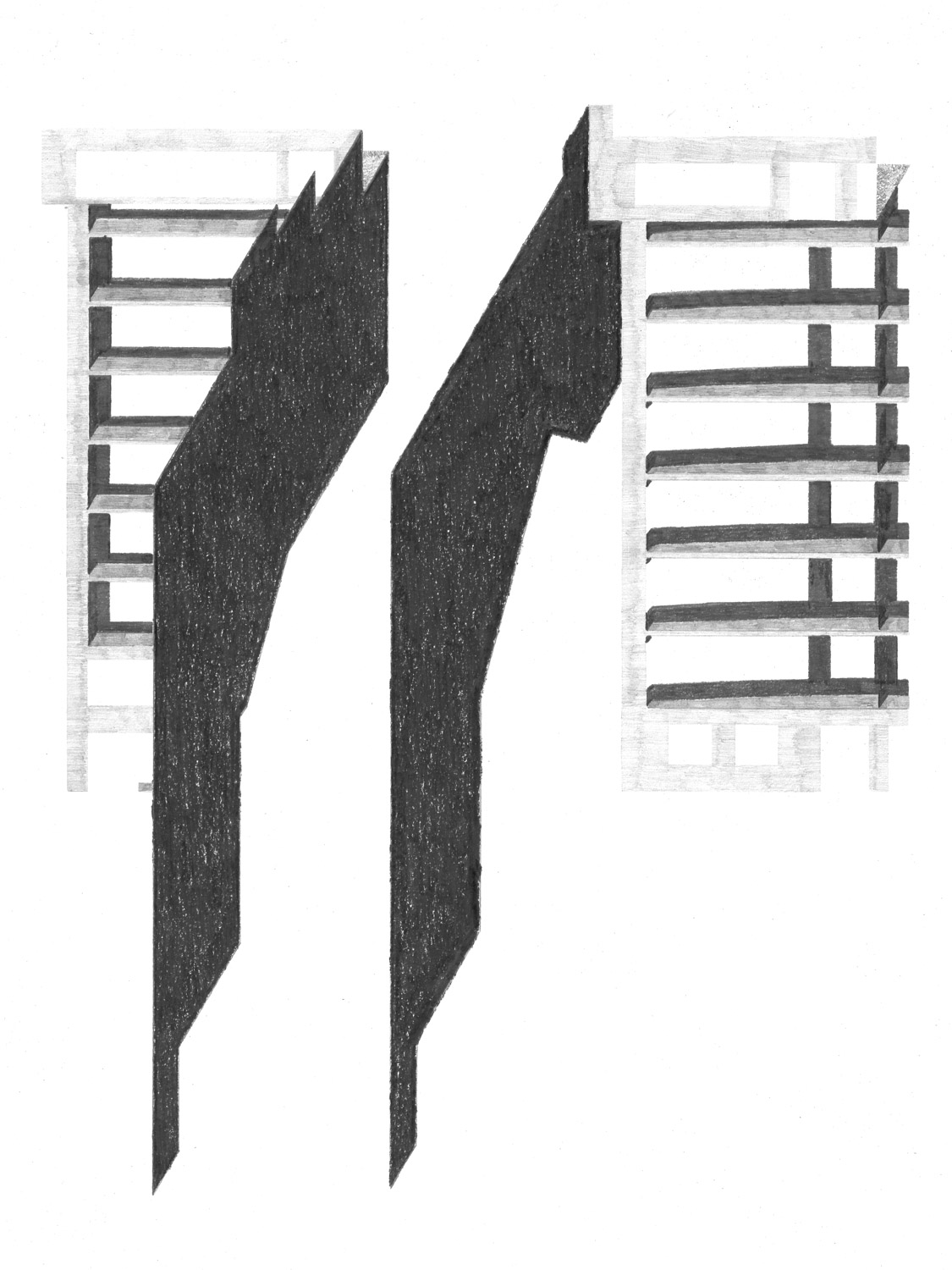

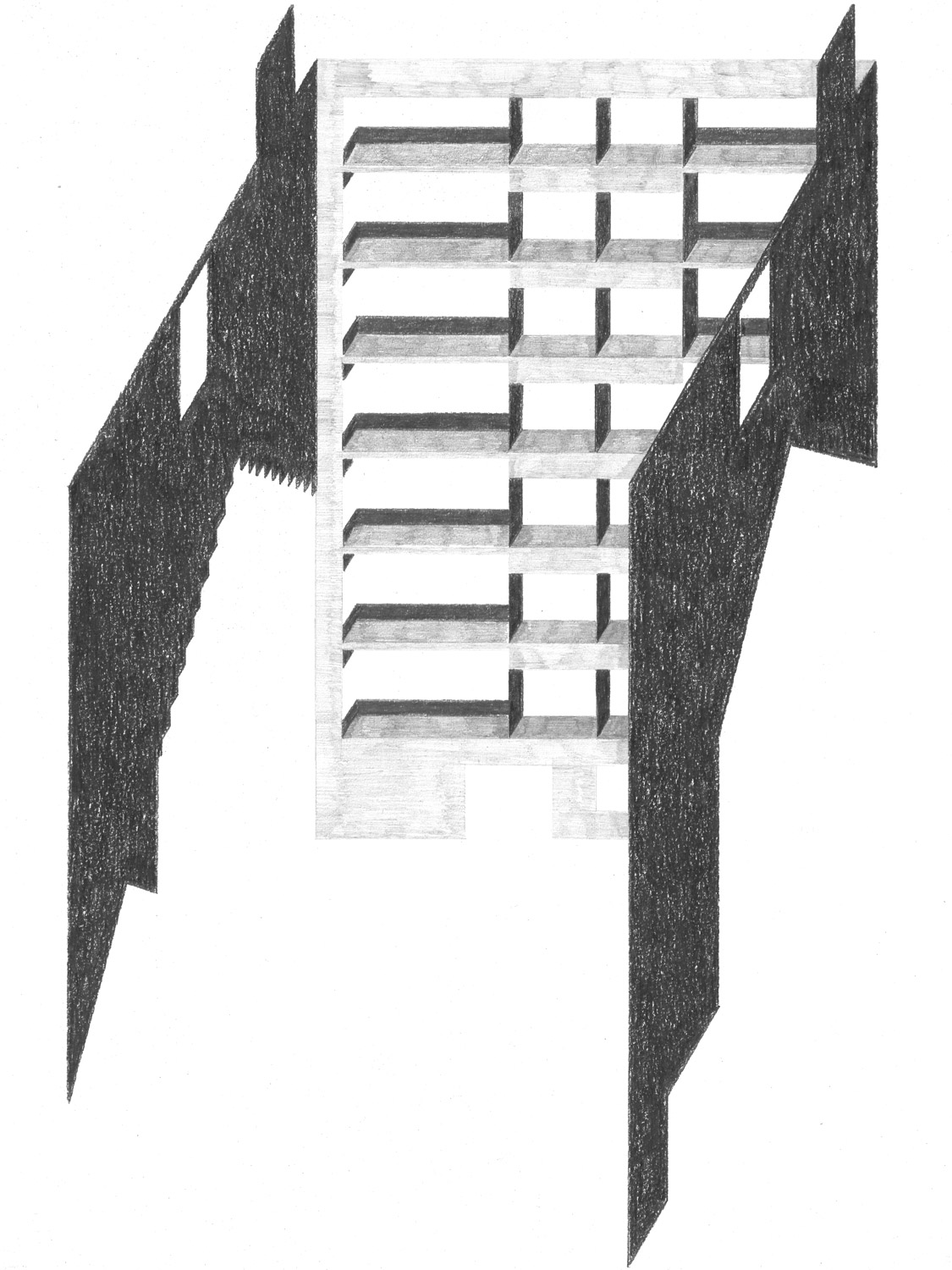

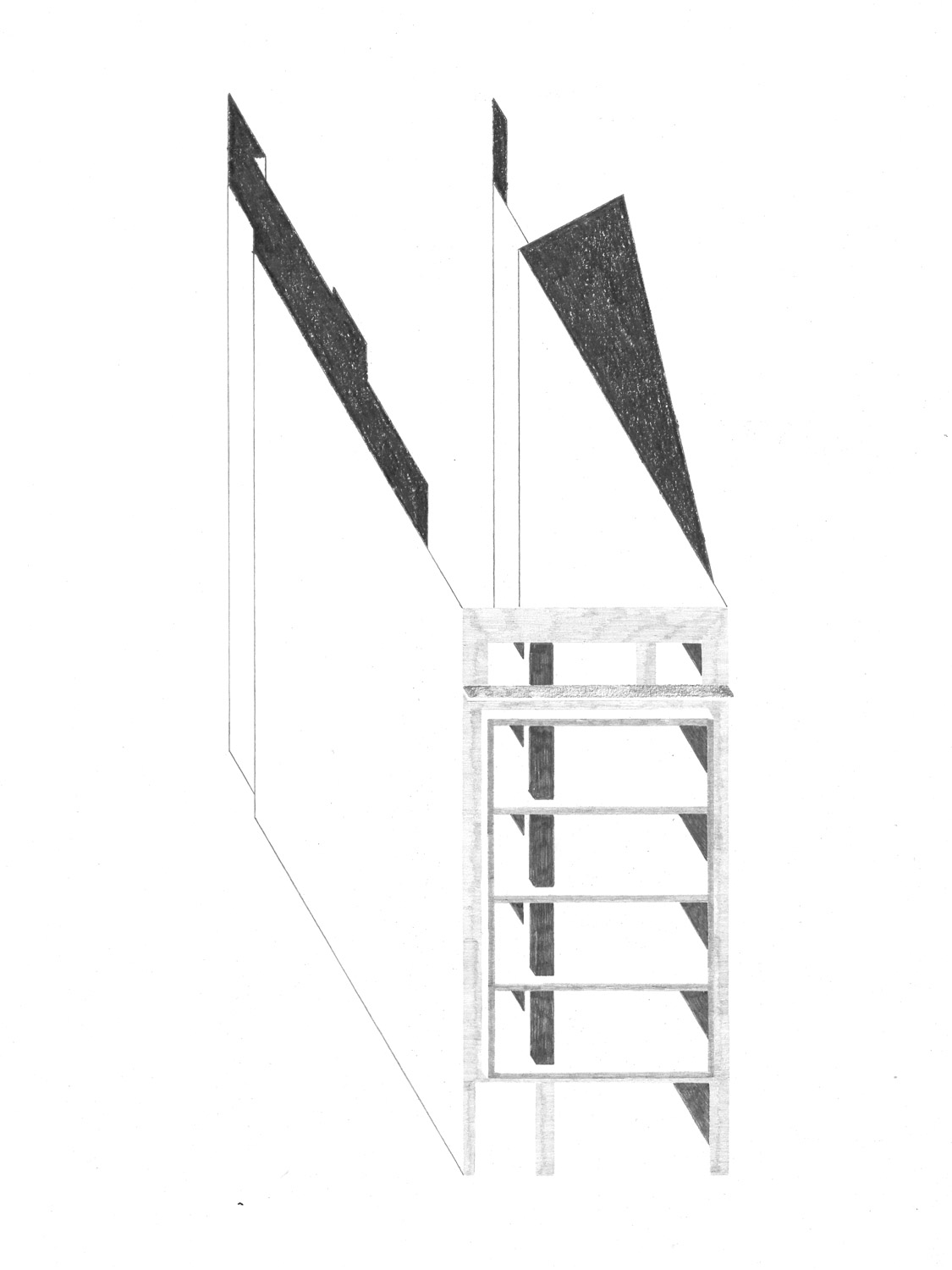

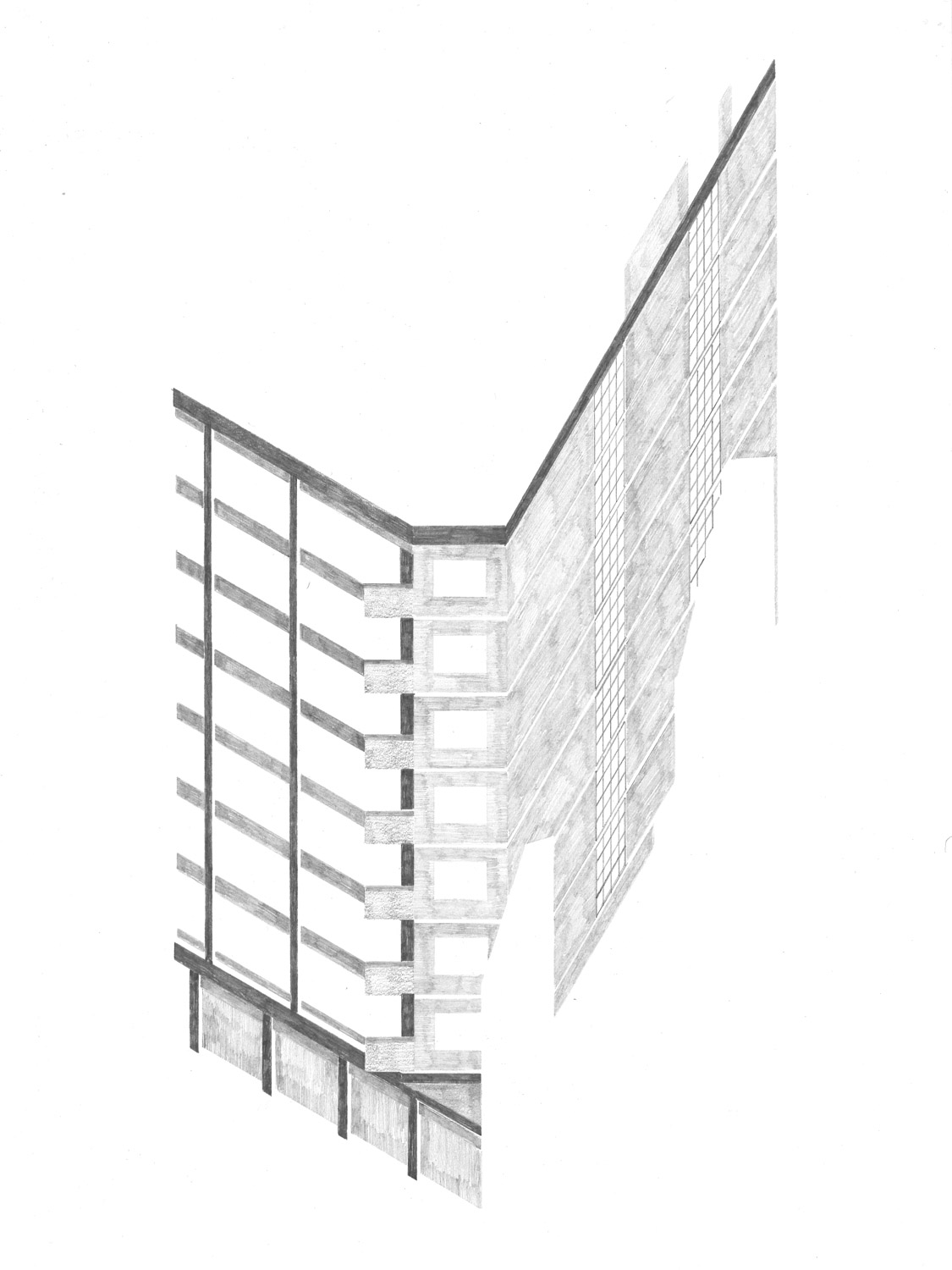

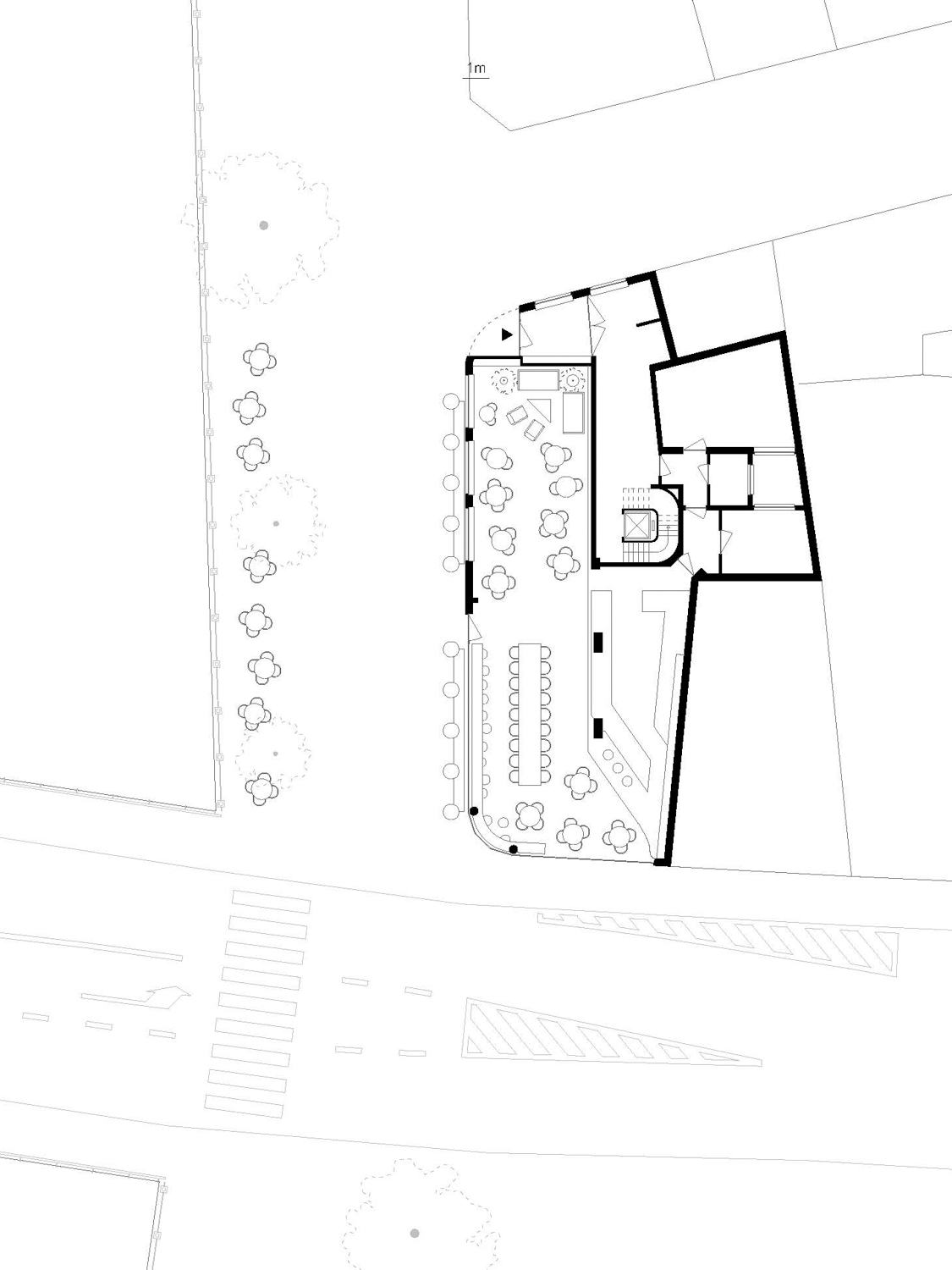

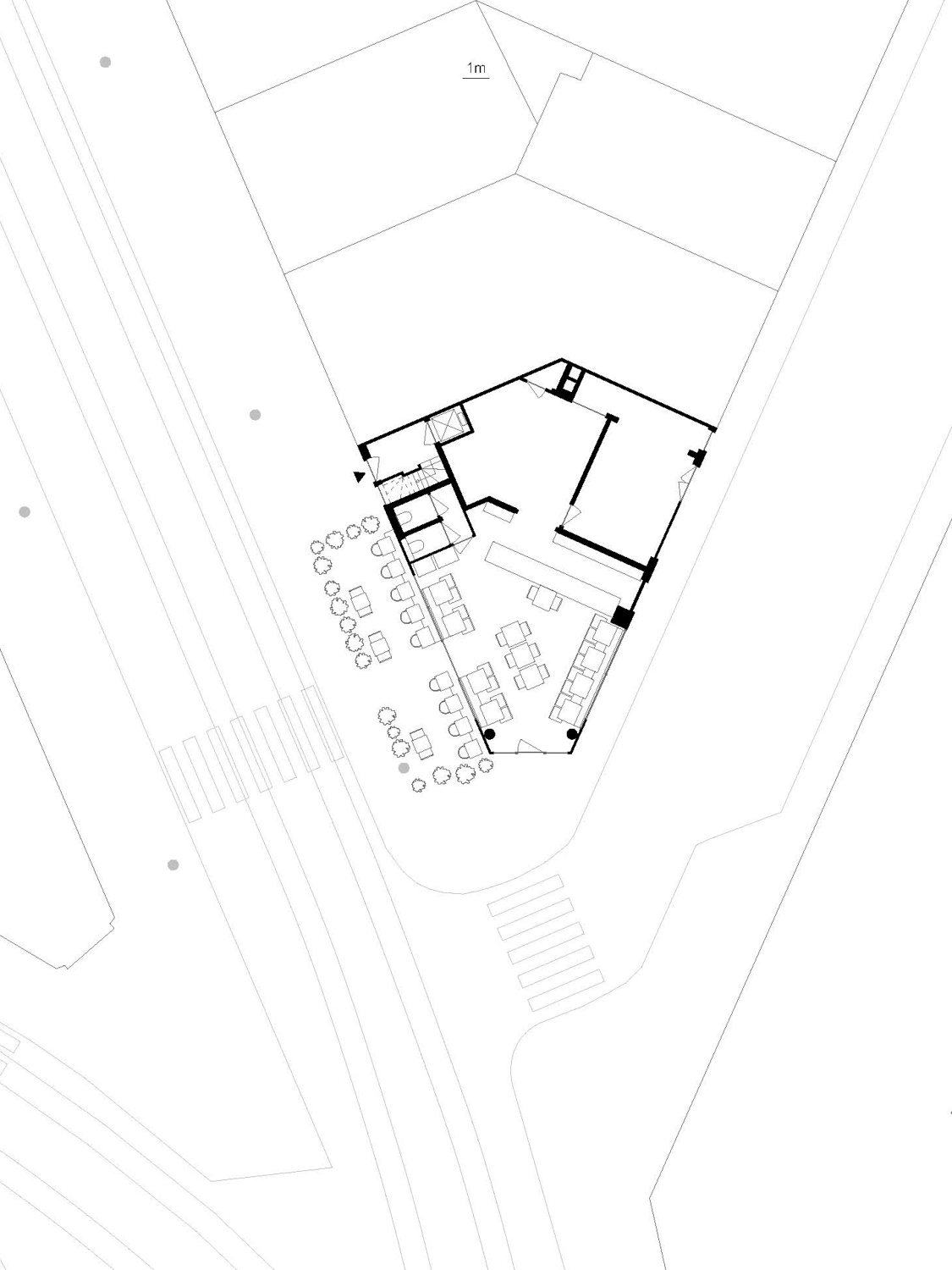

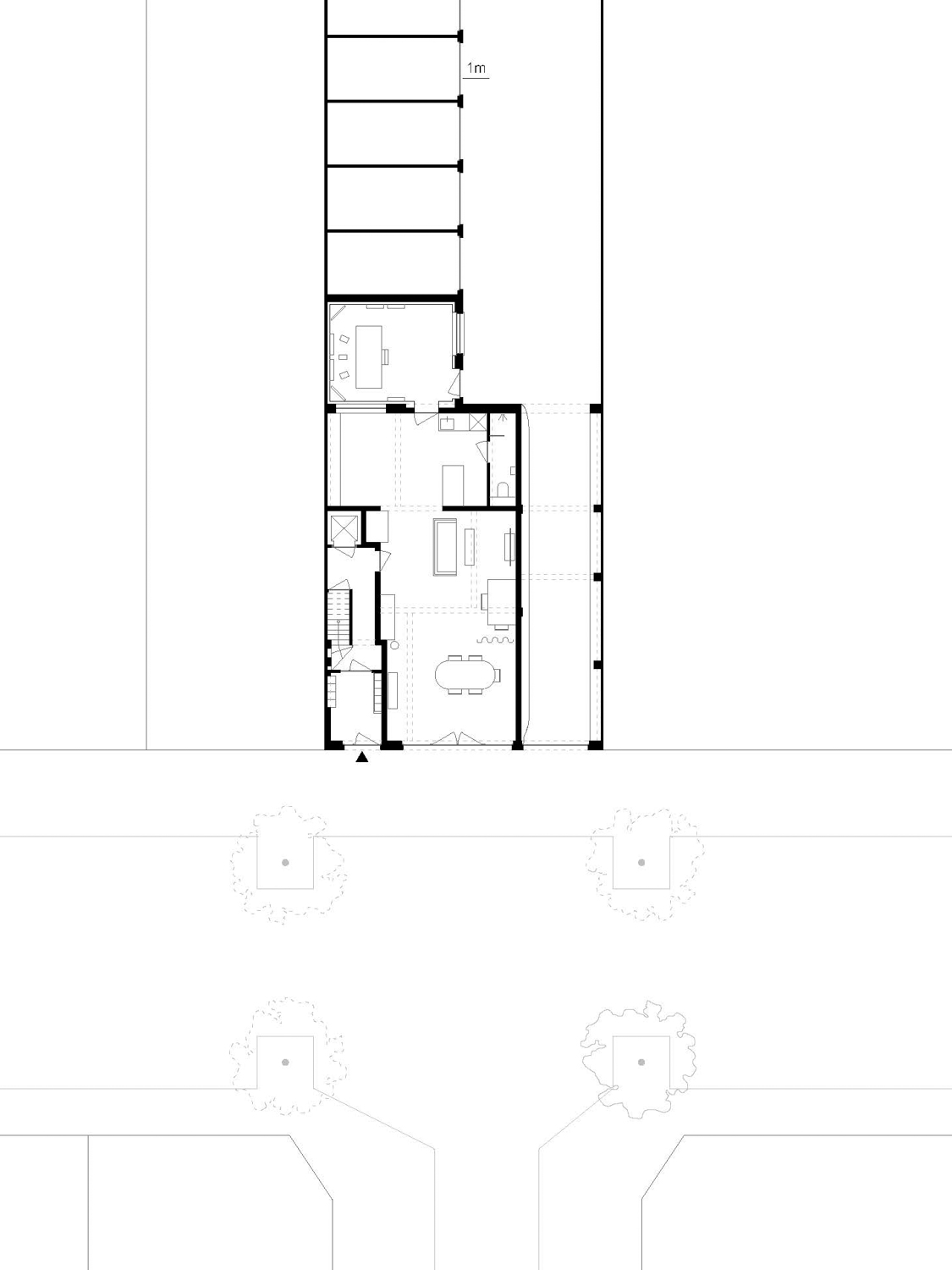

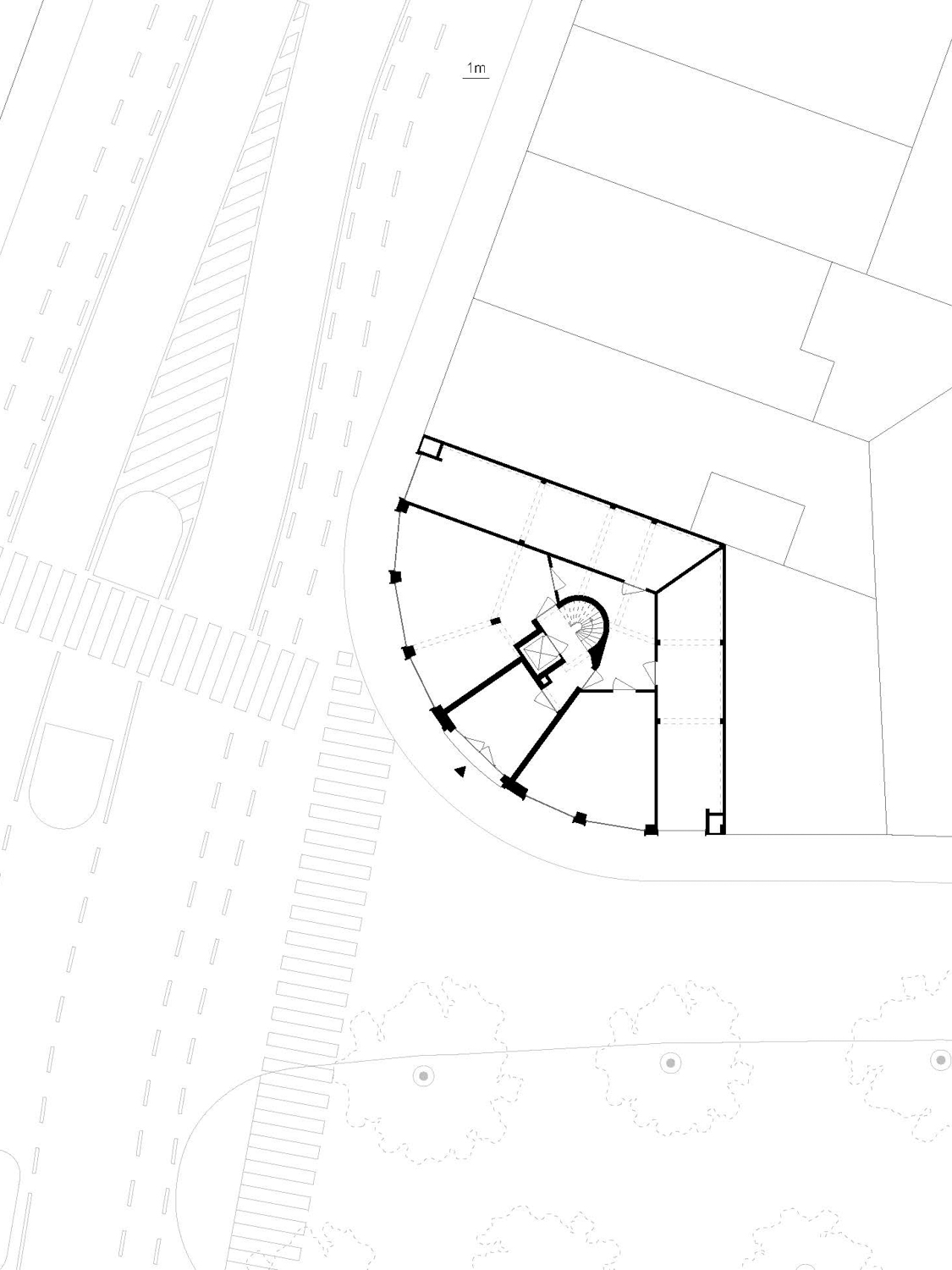

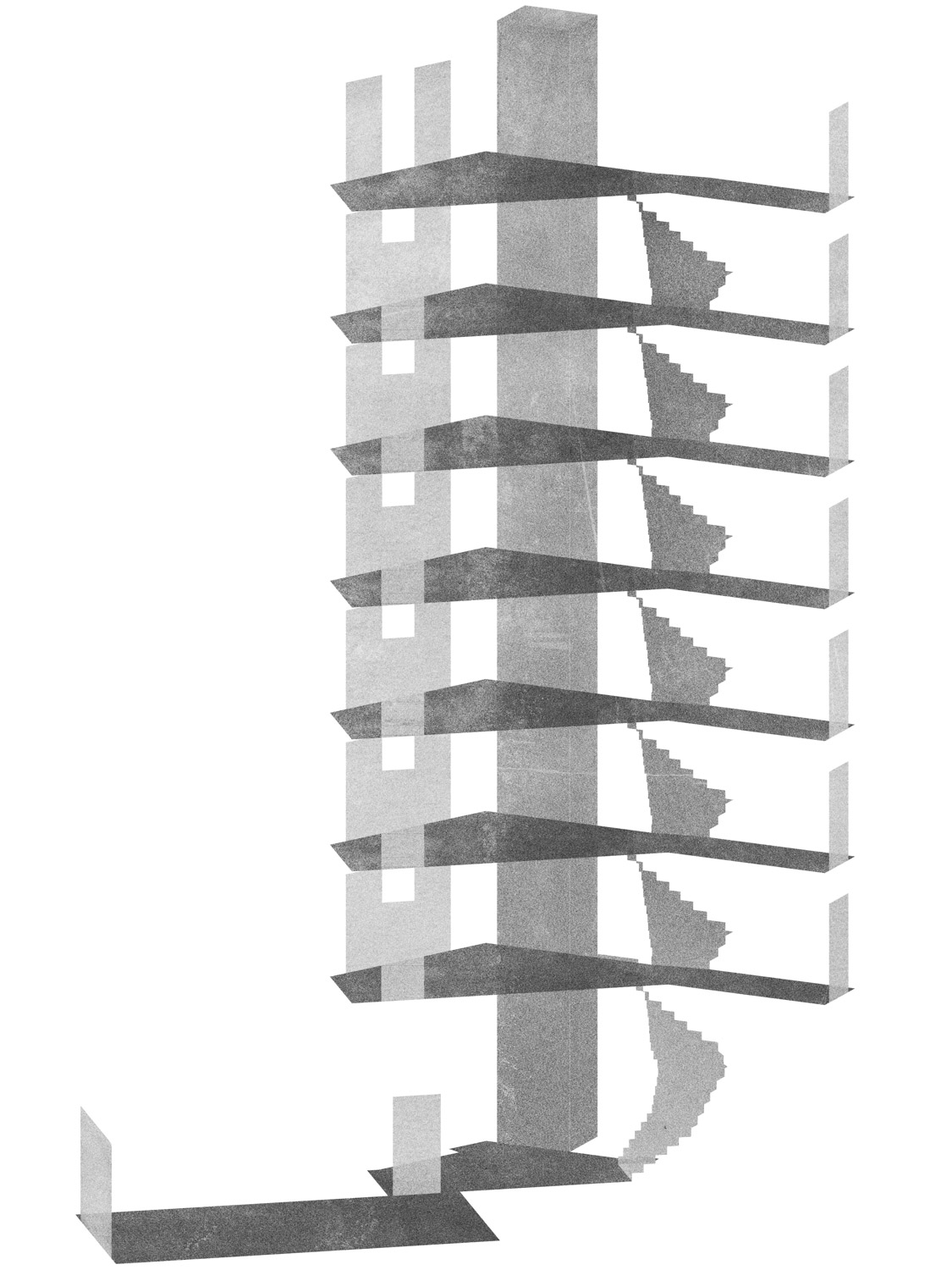

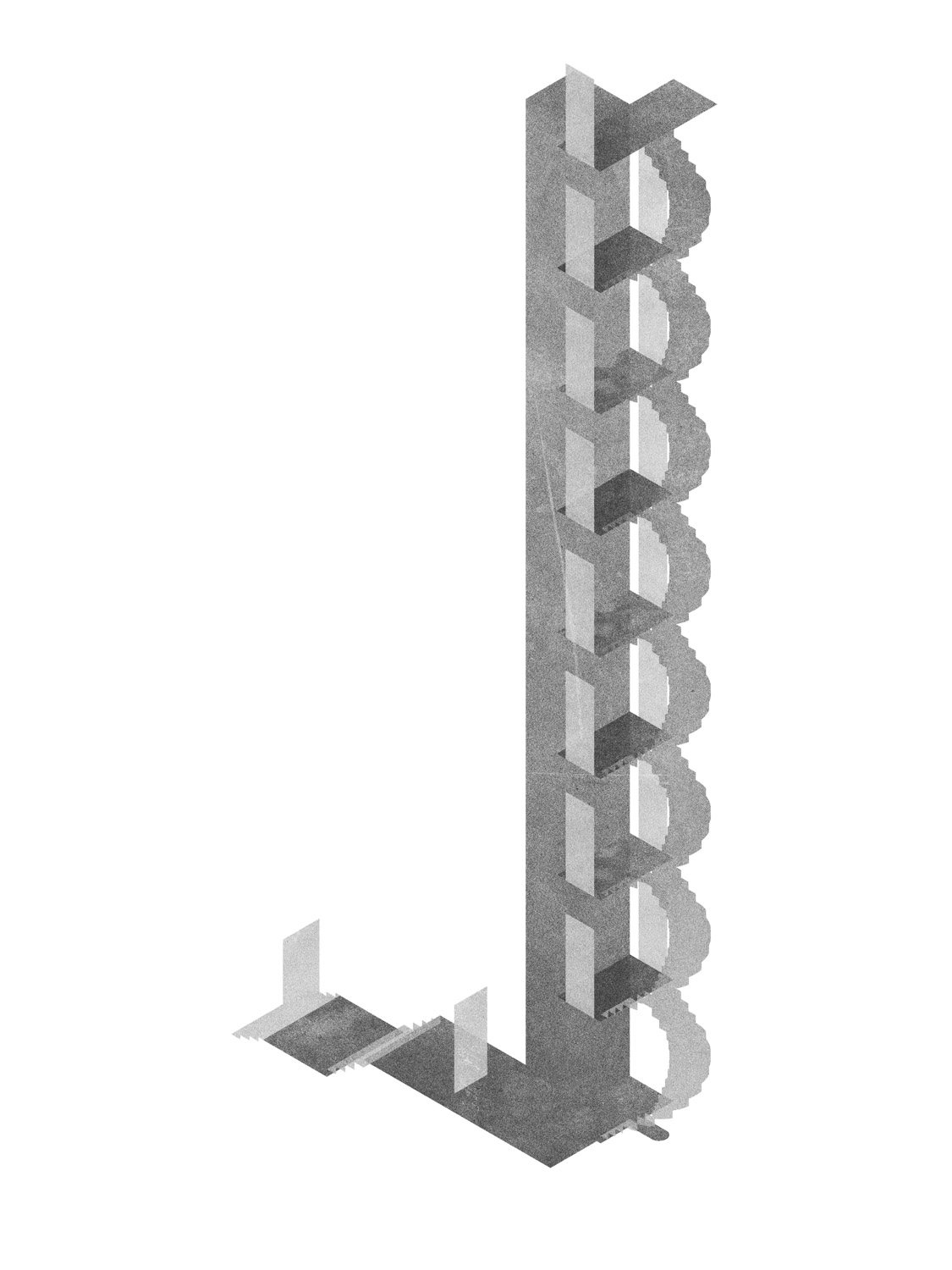

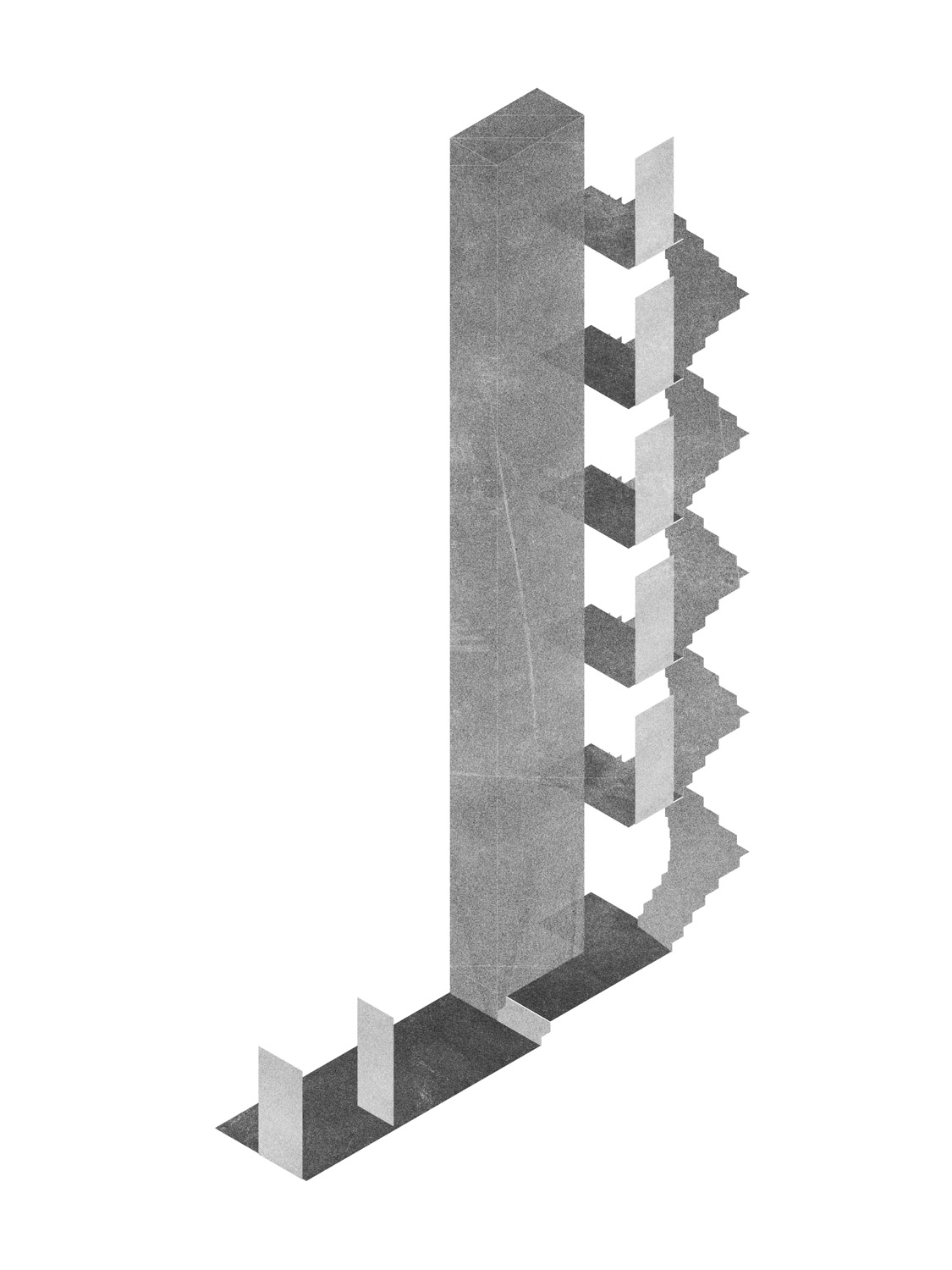

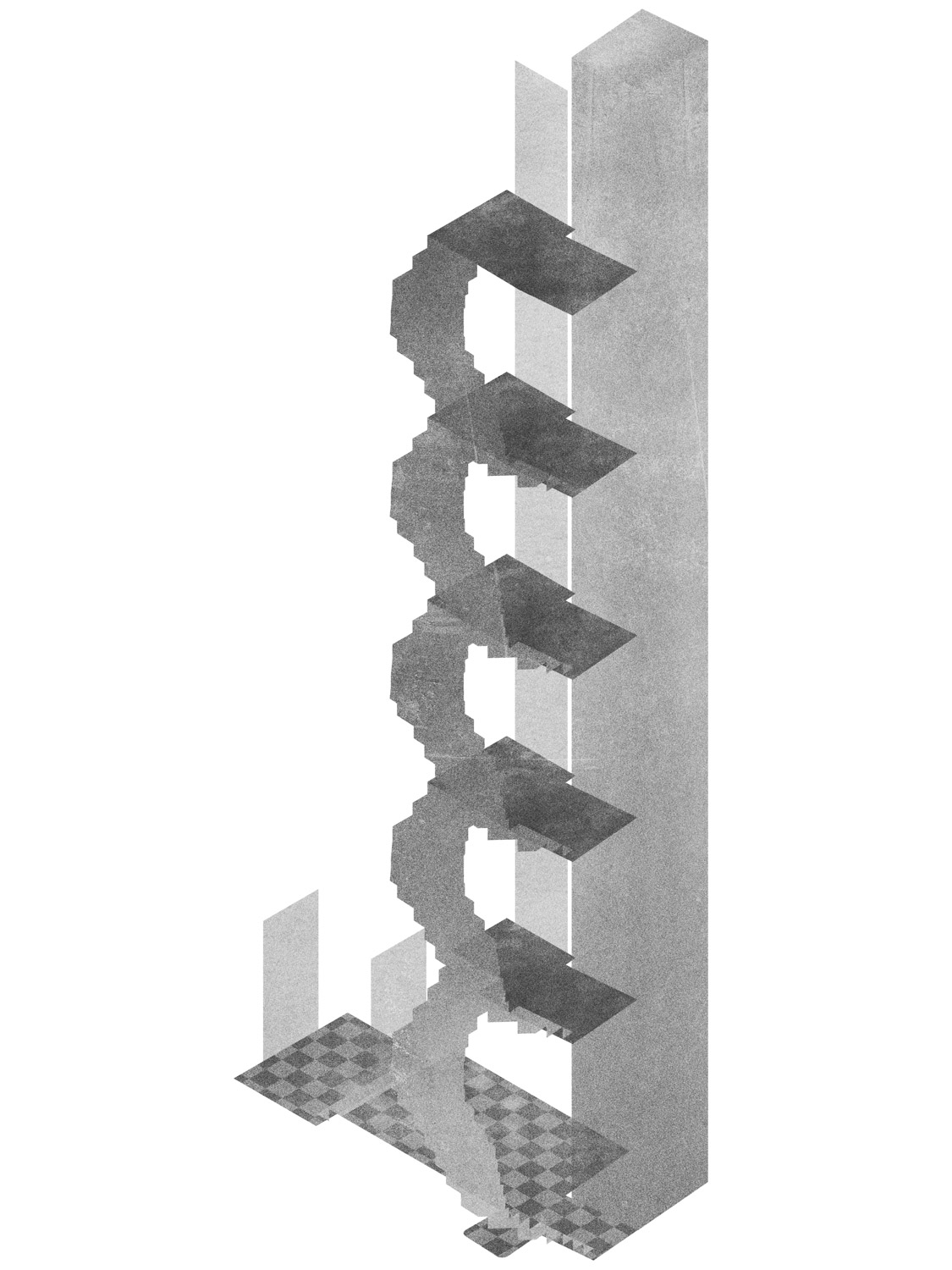

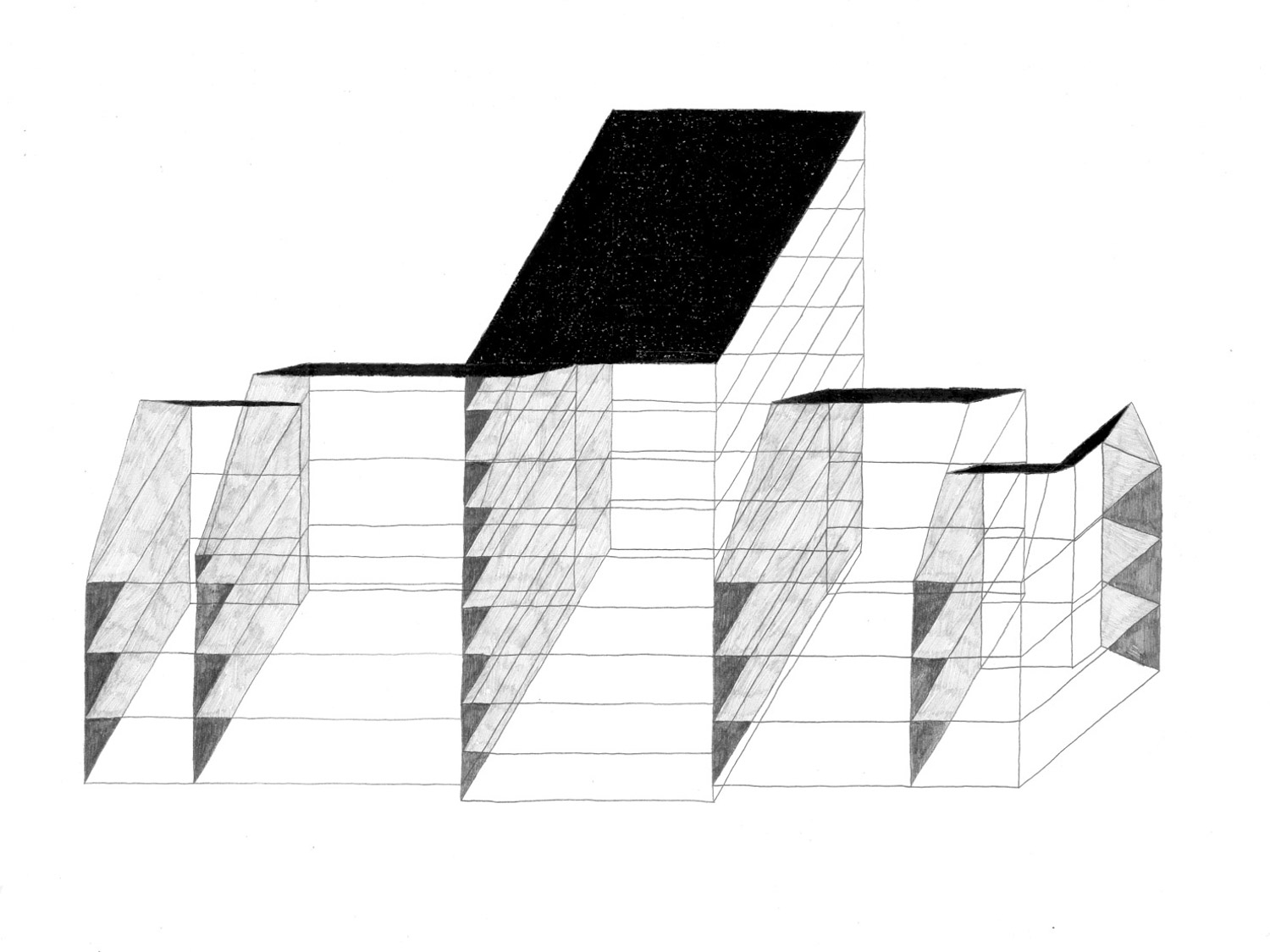

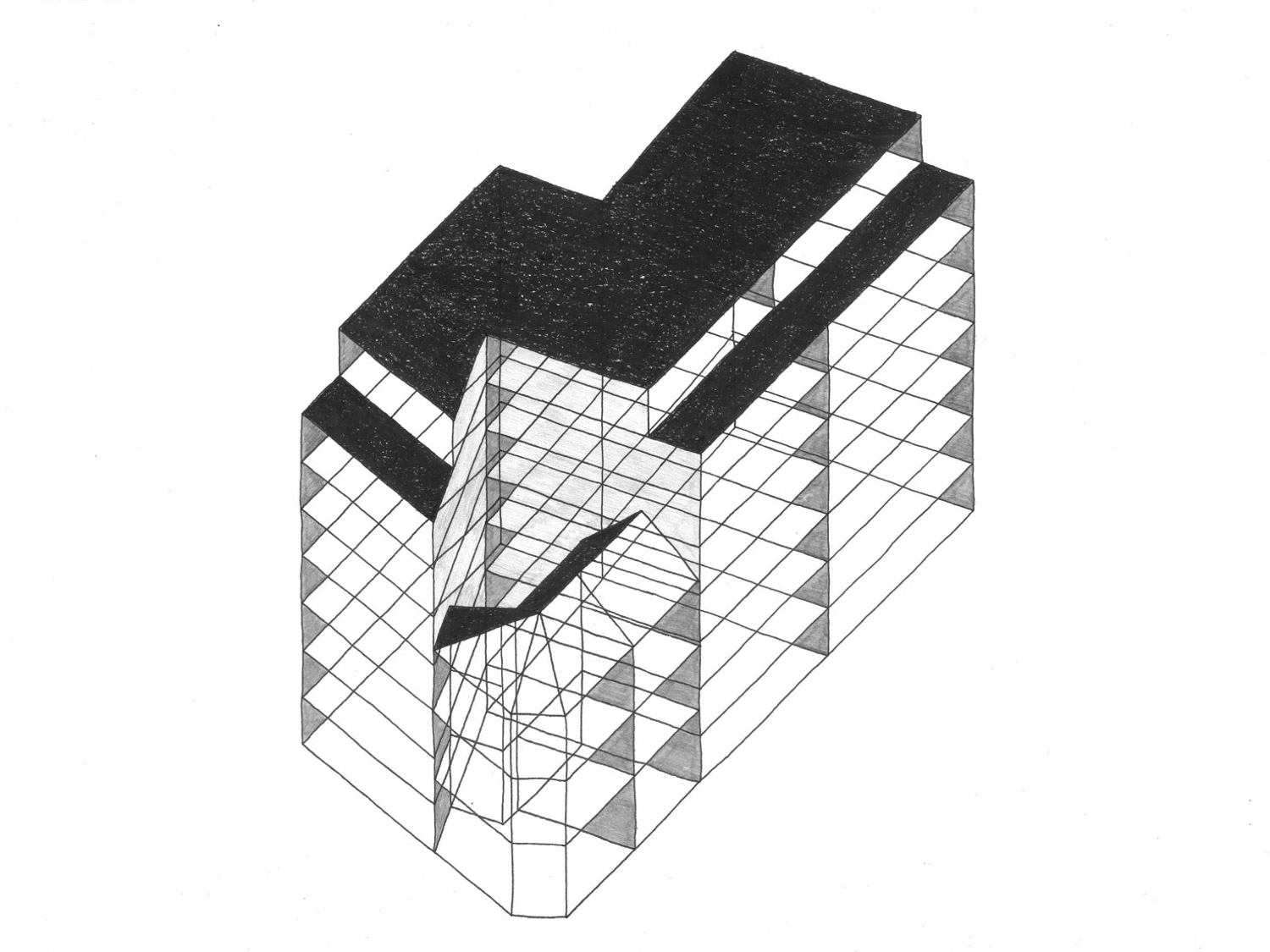

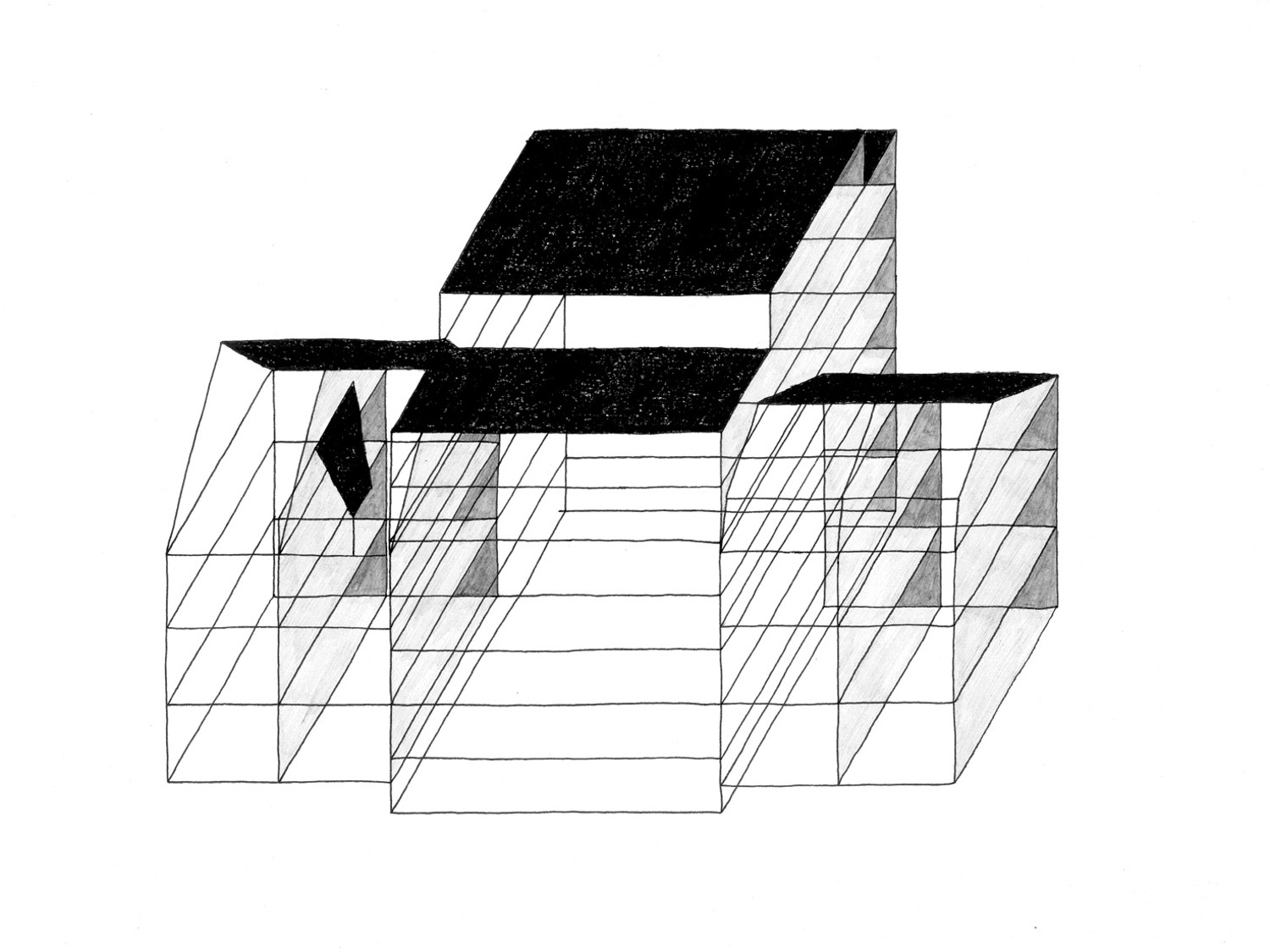

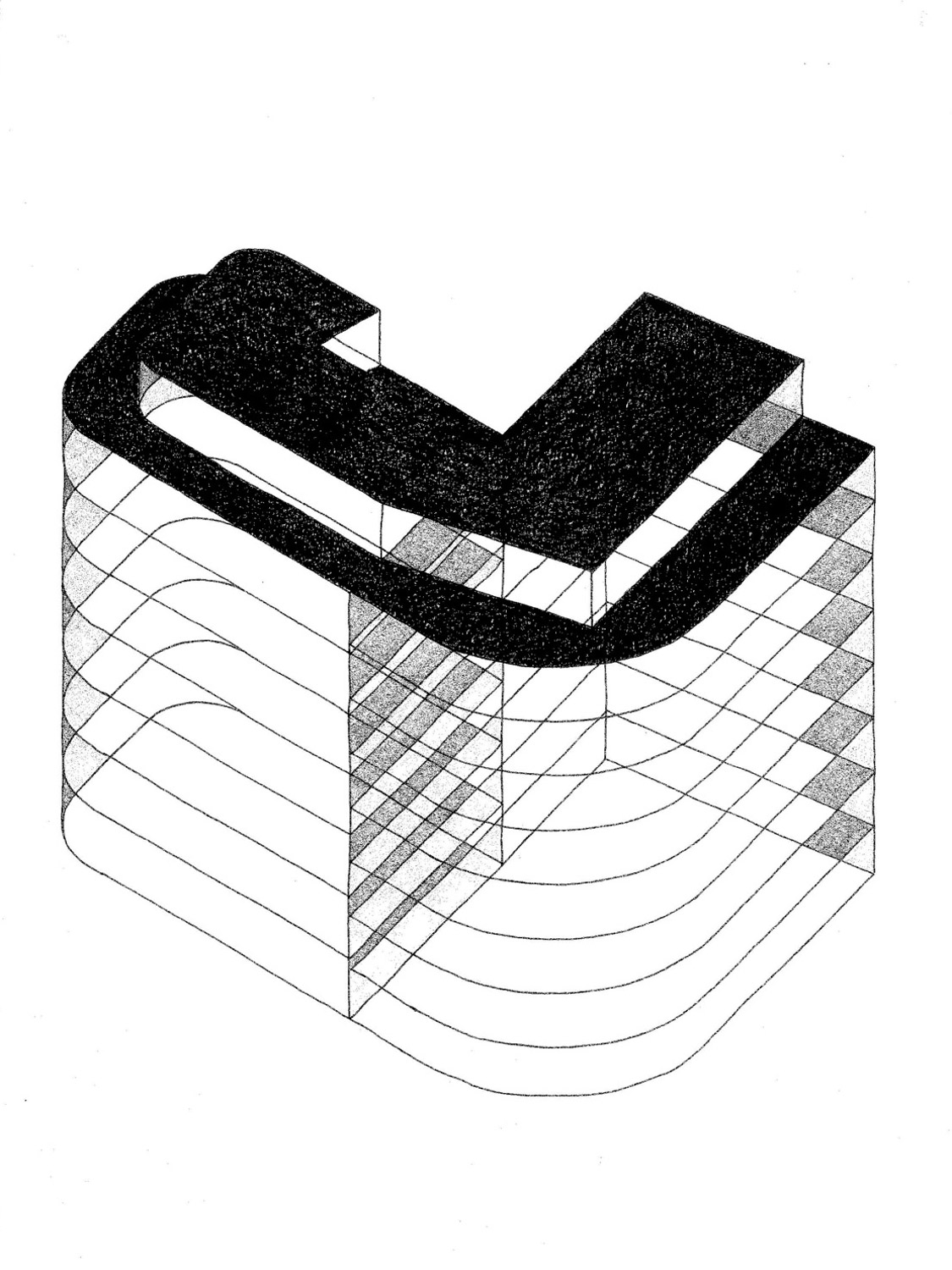

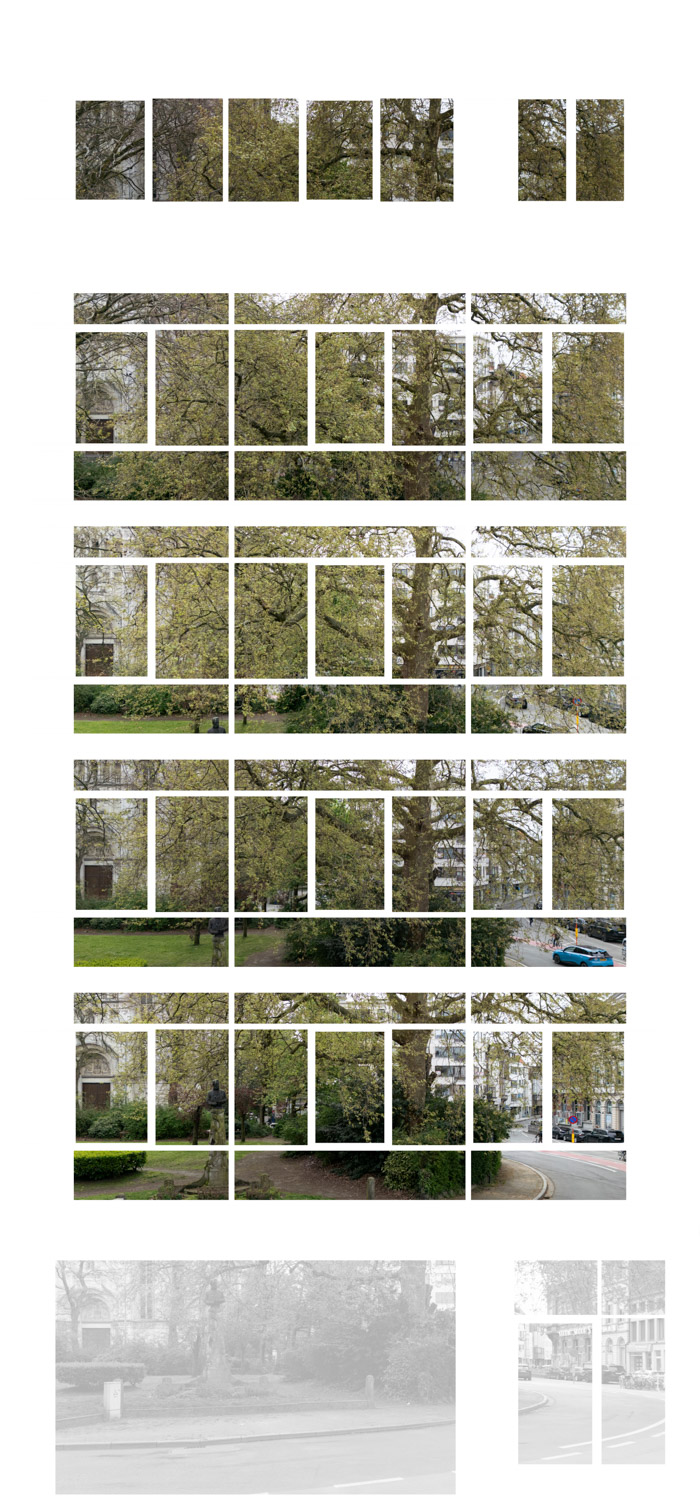

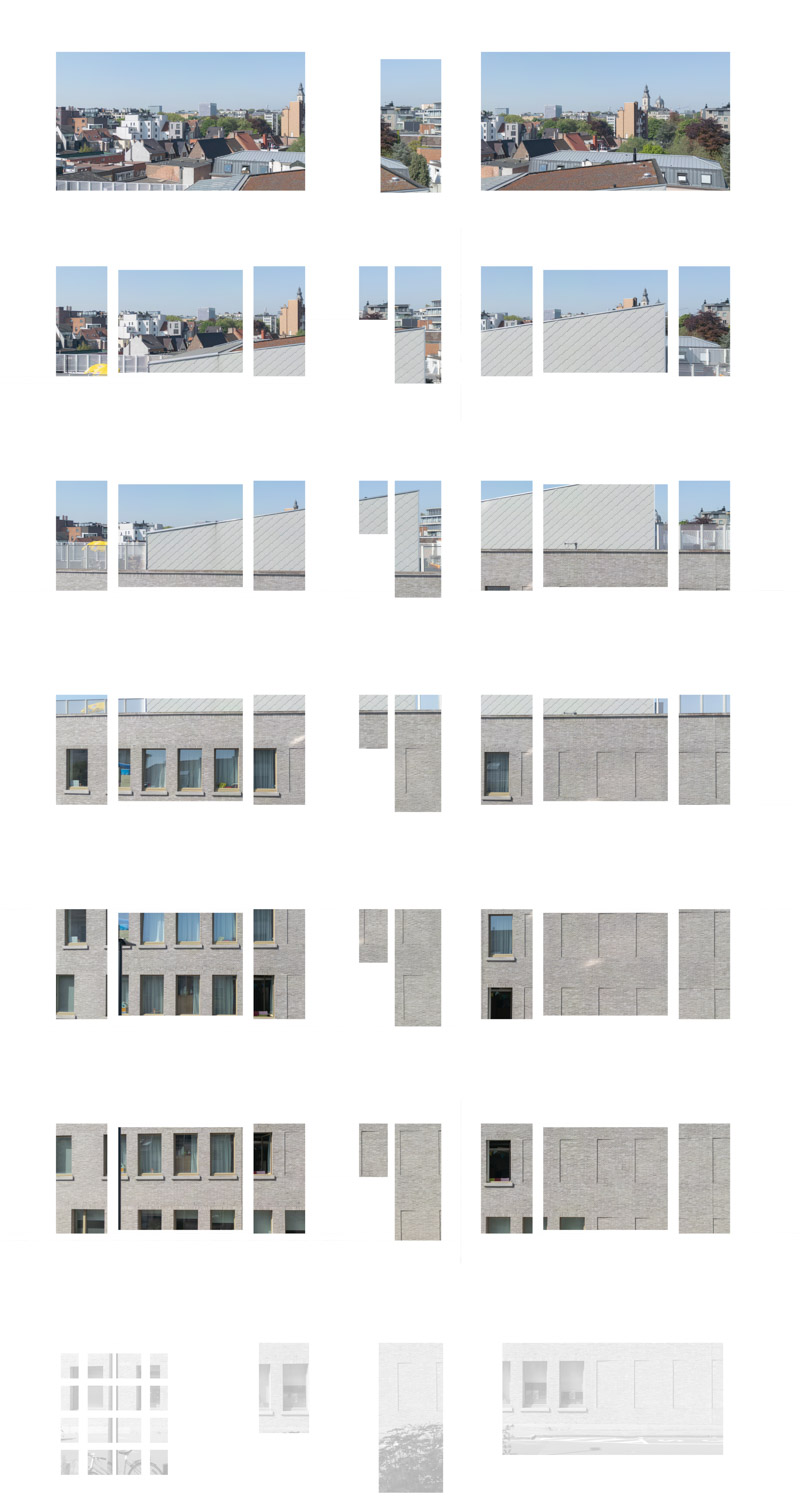

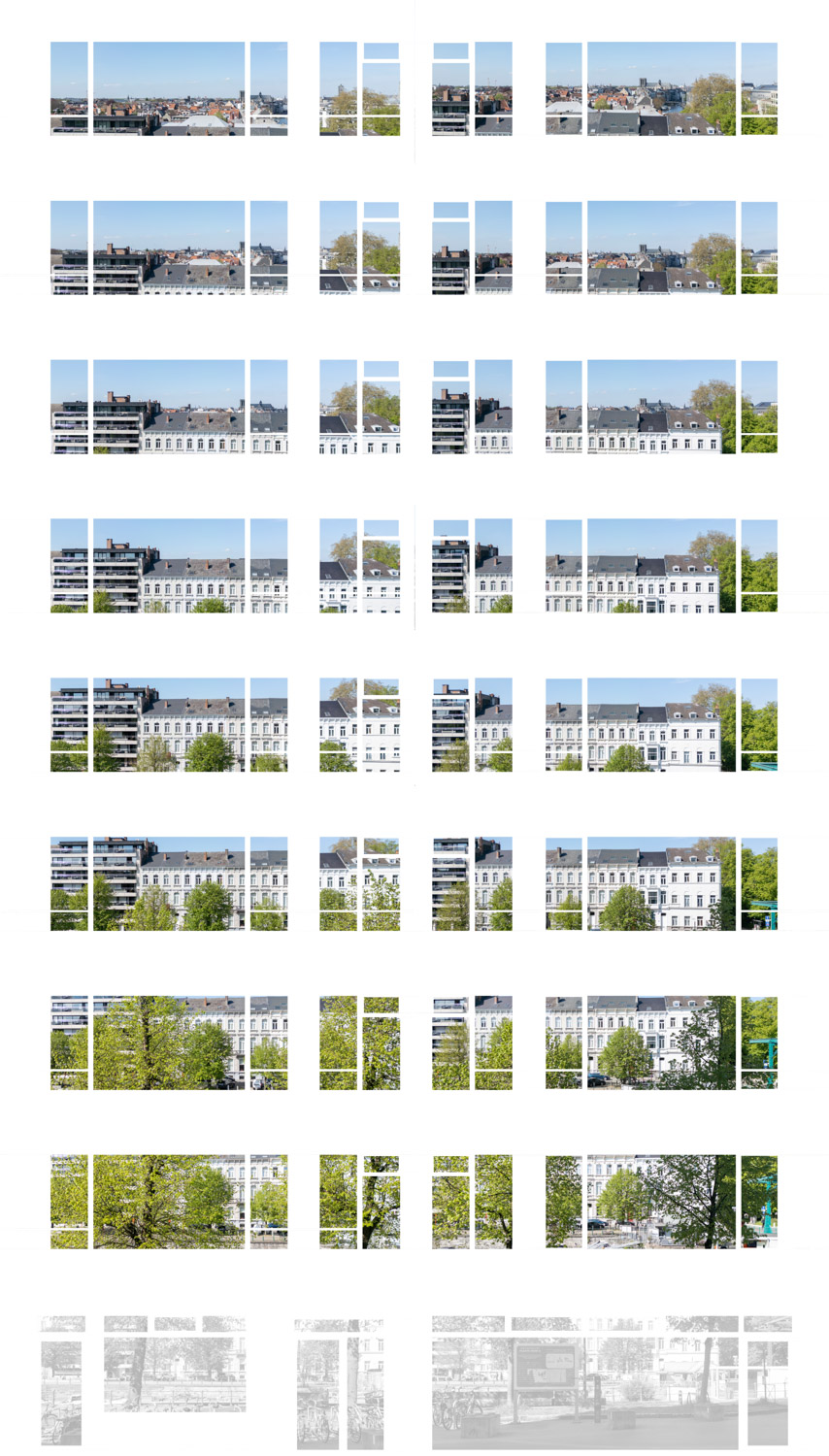

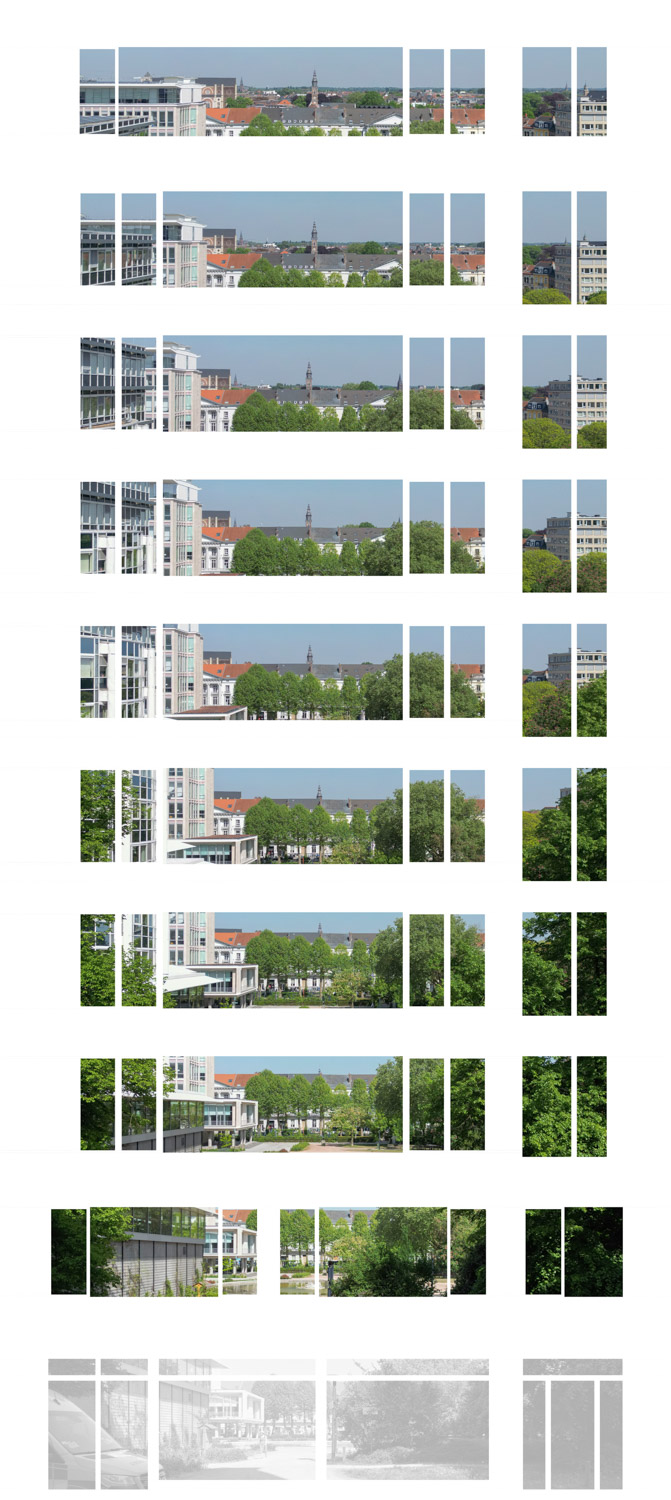

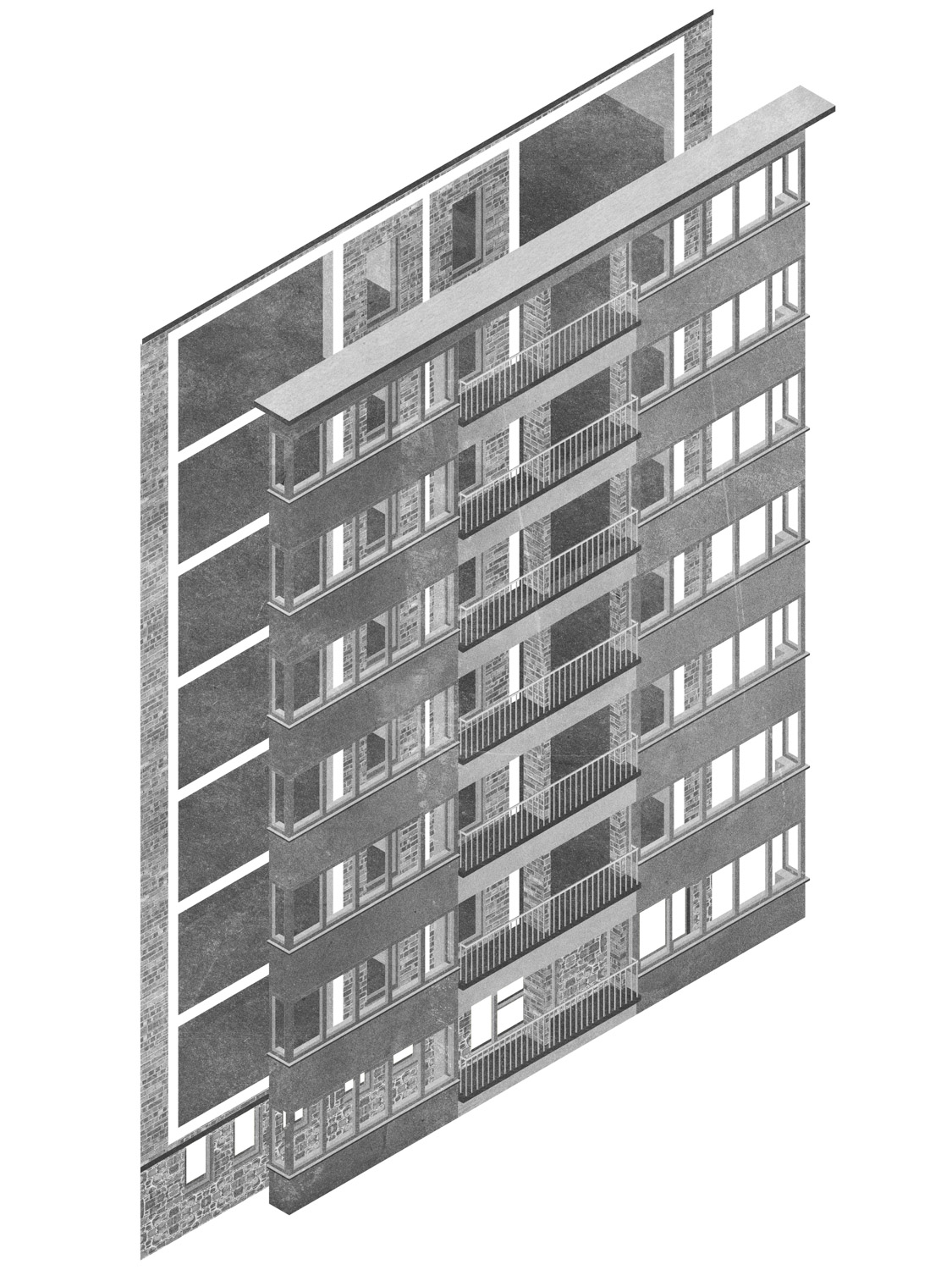

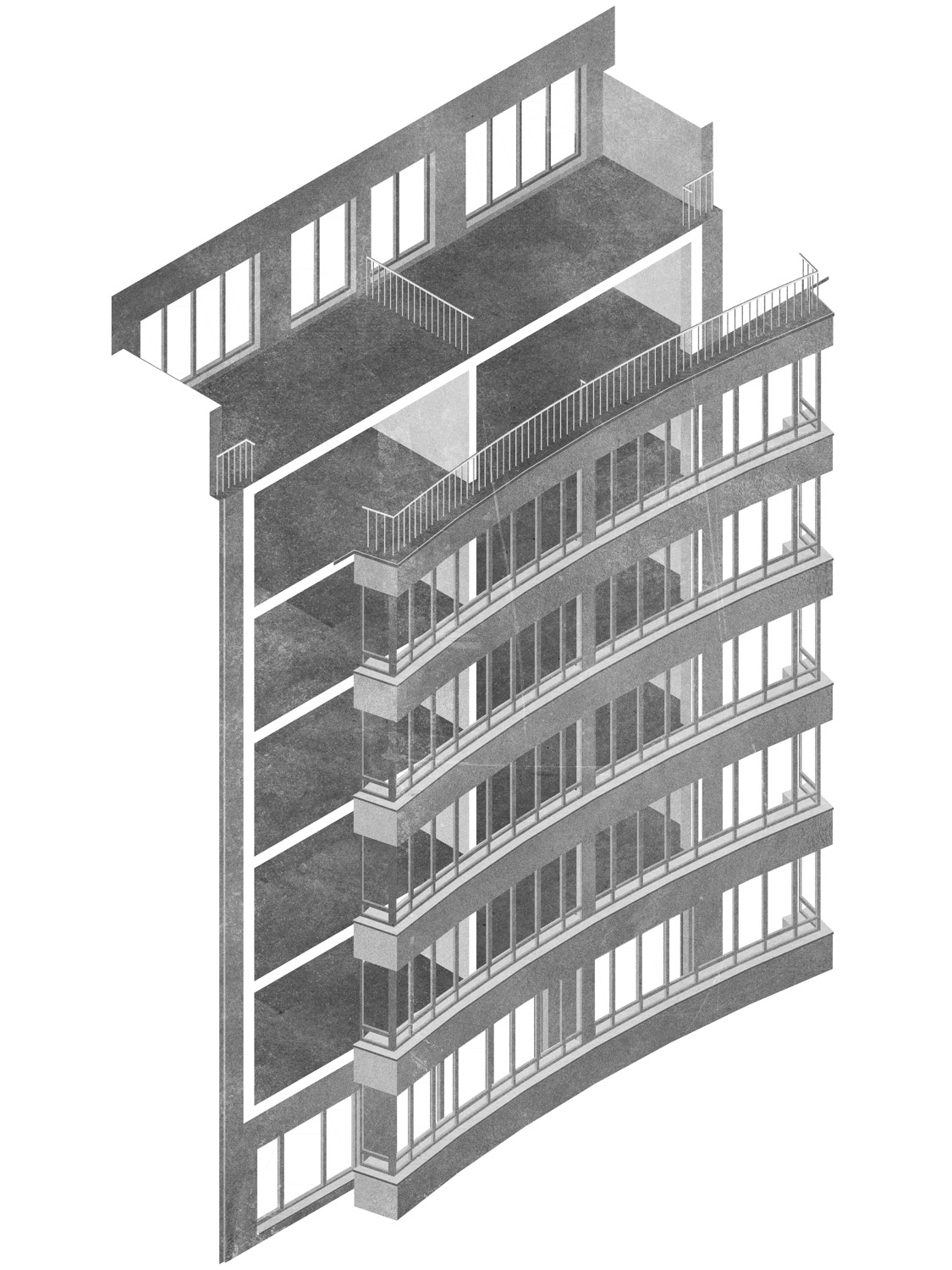

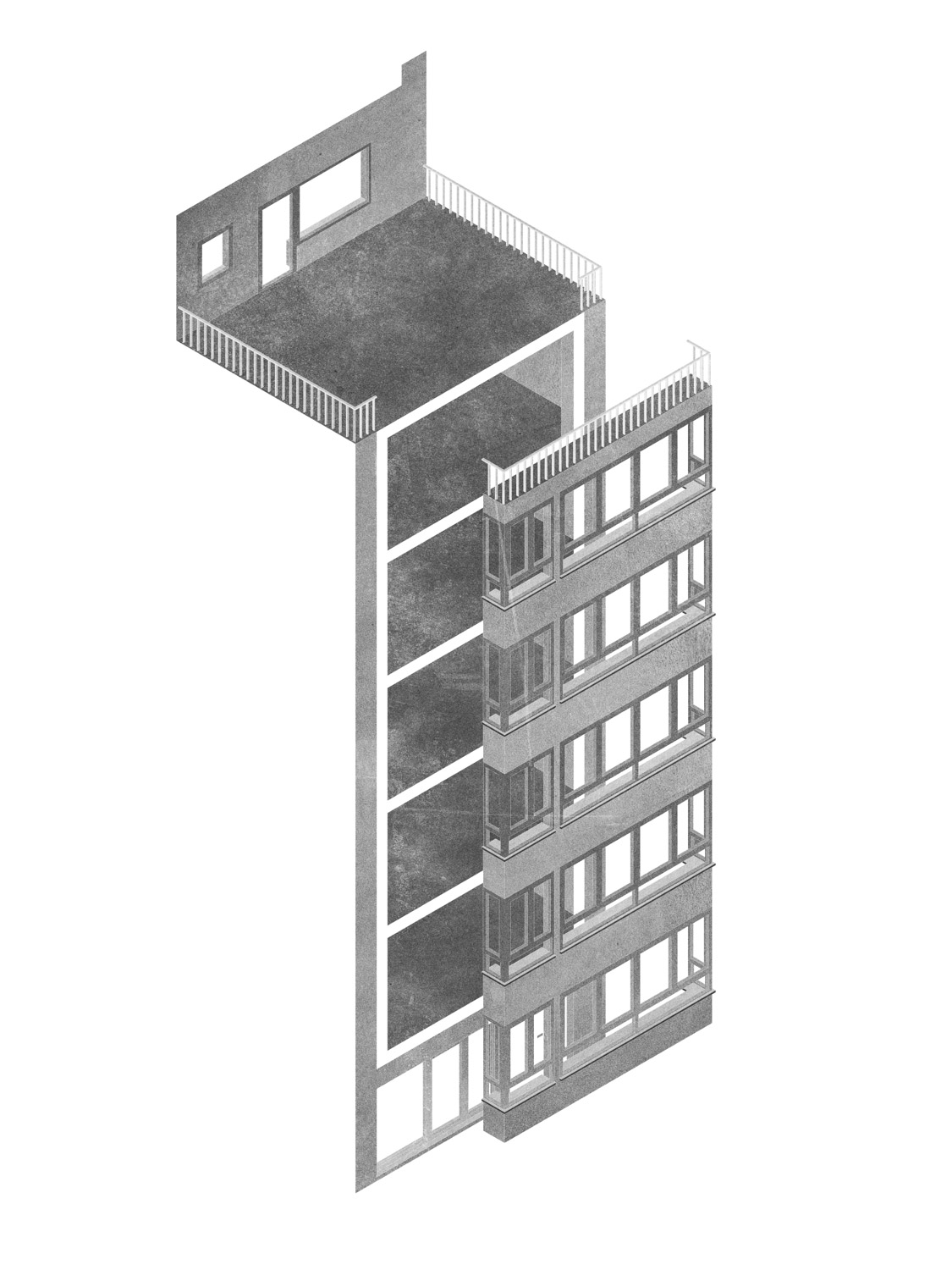

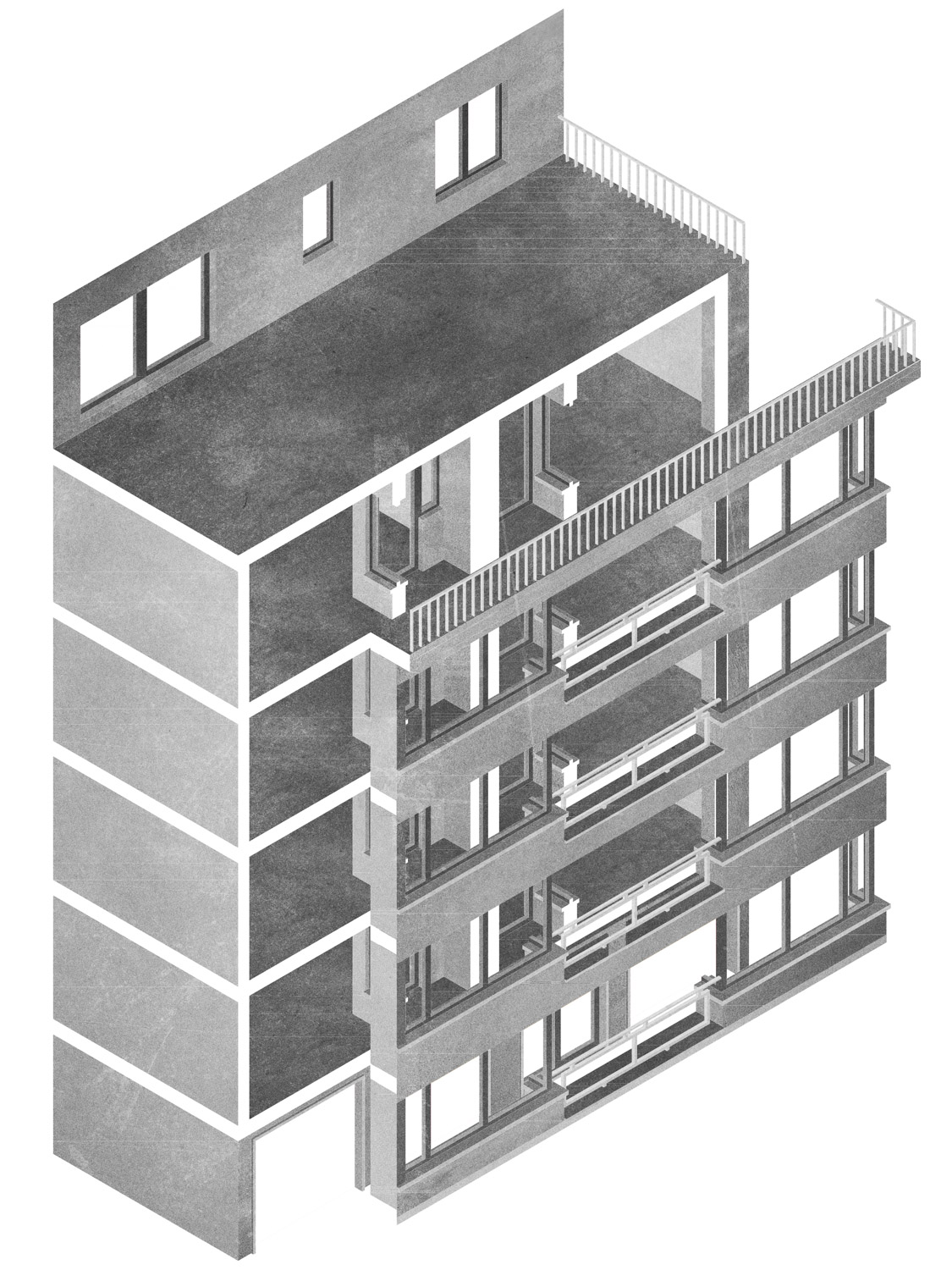

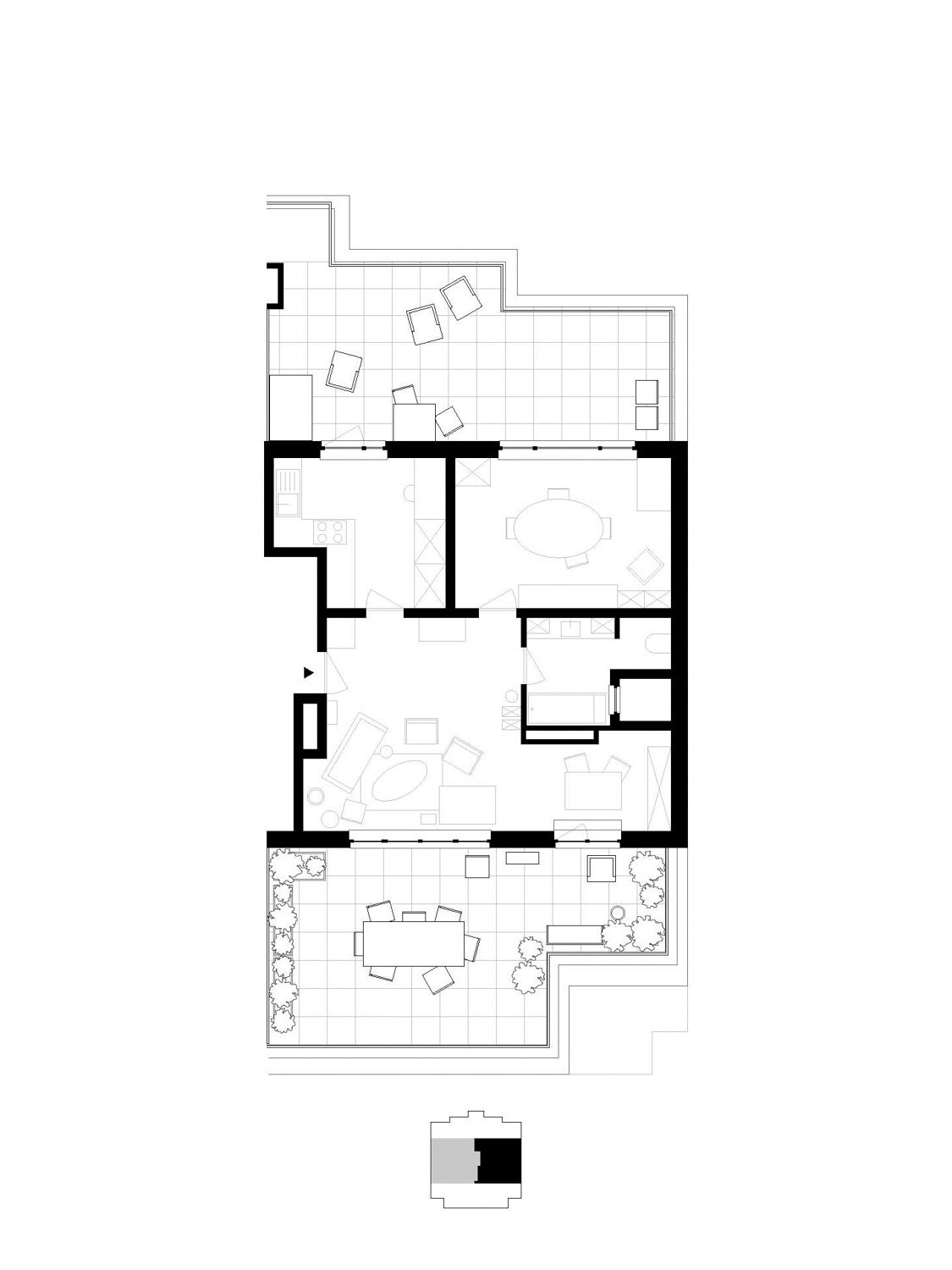

Elf fenomenen vormen hierbij samen een fenomenologie van deze typologie. Elk fenomeen wordt eerst gekaderd en vervolgens verbeeld aan de hand van enkele cases: hierbij staan nooit de gebouwen zelf centraal, maar ligt de focus op karakteristieke eigenschappen die zich binnen of buiten die gebouwen manifesteren, telkens op een schaal die relevant is voor het fenomeen. Een bijzondere focus ligt hierbij op fotografie en tekening, in een zoektocht naar manieren om de fenomenologie die deze typologie heeft voortgebracht visueel te vatten.

De masterproef wil geen normatief oordeel vellen, maar biedt informatie en een aantal instrumenten aan waarmee de lezer zelf een waardering kan opbouwen. Tegelijk bevat ze een waarschuwende ondertoon: zonder zorgvuldige benadering dreigt een belangrijke laag van het stedelijk weefsel te verdwijnen onder een generieke verduurzamingstaal. Dit werk wil een eerste schakel zijn in een hernieuwde waardering en benadering van deze vaak miskende typologie.

This master’s thesis explores the typology of the ‘invisible giants’ in Ghent: apartment buildings that in the 1960s and 1970s, led by major developers such as Amelinckx and Etrimo, flooded Belgian cities and have largely remained outside architectural attention to this day. The thesis focuses explicitly on the broad production of such developments, not only on the work of a few major players.

It starts from the existing patrimony and looks at how these designs, originally conceived from a very specific, rational approach, are inhabited, experienced, and valued today. The thesis does not aim to make a detailed historical reconstruction or to formulate a fully developed vision for the future, but attempts a re-reading. Through observations, conversations with residents, and visual representations, it seeks a new approach to this typology.

Eleven phenomena together form a phenomenology of this typology. Each phenomenon is first framed and then illustrated with a few cases: the buildings themselves are never the focus, but rather characteristic properties that manifest inside or outside the buildings, each on a scale relevant to the phenomenon. A special focus is on photography and drawing, in search of ways to visually capture the phenomenology produced by this typology.

The thesis does not seek to pass normative judgment, but provides information and tools with which the reader can build their own appreciation. At the same time, it carries a warning: without careful approach, an important layer of the urban fabric risks disappearing under generic sustainability discourse. This work aims to be a first link in renewed appreciation and approach of this often overlooked typology.

In Gent, en bij uitbreiding in zowat alle Belgische grootsteden, bepaalt een arsenaal aan collectieve woongebouwen uit de jaren ‘60 en ‘70 mee het stedelijk landschap. Verspreid in de stad, dikwijls langs grote assen of nabij parkgebied, onderscheidt deze middelhoogbouw zich bij uitstek van haar omgeving. Prominent en alomtegenwoordig, maar tot op heden ook grotendeels genegeerd. Als stedeling blijven we vaak blind voor deze onzichtbare reuzen: onbewust richt onze focus zich op de ‘mooie historische stad’ en laten we deze recentere architecturale productie hoogstens in de perifere zone van ons blikveld toe. Wanneer er over deze woonblokken gesproken of geschreven wordt, worden ze al snel weggezet als lelijk, banaal, karakterloos of schaalverstorend. En toch worden deze gebouwen nog steeds volop bewoond, blijken ze geliefd bij hun bewoners en zijn ze gegeerd op de vastgoedmarkt. Het is binnen dit spanningsveld dat het onderzoek van deze masterproef zich afspeelt.

Voor de aanleiding van deze ontwikkelingen moeten we terug naar het jaar 1962. In de nasleep van de Tweede Wereldoorlog kende België een snelgroeiende woningnood. Steden werden geconfronteerd met een toenemende vraag naar woningen. Tegelijk bood het economische klimaat van de jaren ’60 - gekenmerkt door stijgende rentevoeten en terughoudende overheidsinvesteringen in huisvesting - de private markt steeds meer kansen. Private ontwikkelaars, Amelinckx en Etrimo voorop, kregen vanaf dan de mogelijkheid om zelf te voorzien in huisvesting voor de brede middenklasse en hun ontwikkelingsmodel door te duwen1, wat leidde tot verdichting en uitbreiding van het stedelijk weefsel2. Cruciaal hierin was de “Wet van 29 maart 1962 houdende organisatie van de ruimtelijke ordening en van de stedenbouw”, die een instrumentarium introduceerde en de verantwoordelijkheid voor ruimtelijke planning bij de overheid legde. Dit betekende een belangrijke wending voor een land dat voordien geen uitgesproken planningstraditie kende.

Het gebruik van bijzondere plannen van aanleg (BPA’s) die lokale besturen de mogelijkheid boden om de bestemming en inrichting van delen van hun grondgebied vast te leggen, nam in die periode sterk toe. De BPA’s die toen ontstonden, stonden vaak hogere bouwhoogtes toe dan voorheen gebruikelijk was en maakten zo de ontwikkeling van deze middelhoogbouw mogelijk.

In delen van Gent waar geen BPA’s voor handen waren, werden bouwaanvragen beoordeeld door het college van burgemeester en schepenen. Voor interpretatie vatbare bouwkundige regels, de aantrekkingskracht van moderne stadsontwikkeling waarmee politici zich in die periode graag lieten associëren en druk vanuit de private vastgoedsector brachten een stroom aan uitzonderingen voort. Ironisch genoeg vond deze moderne typologie zo vooral haar inplanting in een stadsmodel dat door de grondleggers van datzelfde modernisme net verguisd werd.

In de jaren ’80 riep een ommekeer in het beleid, voortvloeiend uit een hernieuwde aandacht voor de historische stad, deze architectuurproductie een halt toe. BPA’s werden herzien en een uitgebreide inventaris van onroerend erfgoed maakte de verdere ontwikkeling van dit soort gebouwen quasi onmogelijk. Het resultaat is een stedelijk landschap dat tot op vandaag gekenmerkt wordt door een enigmatische mix van collectieve hoogbouw en klassieke architectuur die dichter bij de grond blijft.

Vandaag bevinden we ons op een kantelpunt. Deze onzichtbare reuzen, die ooit het vooruitgangsdenken van hun tijd belichaamden, zijn inmiddels 50 jaar of ouder en naderen het einde van hun levensduur. Ze stammen uit een andere tijd en visie inzake isolatie, technieken en comfort. Dat maakt hen vandaag uiterst kwetsbaar in hun architecturale verschijning: verduurzamingsoperaties lijken steevast naar een hedendaagse anonieme tussentaal te leiden.

Bovendien maken deze gebouwen een aanzienlijk deel uit van het Gentse woonpatrimonium. Er een exact cijfer op kleven is moeilijk, maar een uitgebreide overzichtscatalogus die eerder werd opgesteld, leert dat er zich meer dan vijfhonderd van deze gebouwen in Gent bevinden3. Een generieke architectuurtaal die deze gebouwen ontdoet van elke eigenheid dreigt zich de komende jaren te verspreiden doorheen de stad, en tegelijk ontbreekt het deze typologie aan een genuanceerd en diepgaand debat dat voorbij normen en cijfers gaat.

Door deze gebouwen op een nieuwe manier te bekijken tracht deze masterproef een aanzet te zijn voor dit debat. Ze onderzoekt de hedendaagse relevantie van deze typologie, reikt de lezer observaties aan, wijst op kwaliteiten en gebreken, en tracht de lezer bovenal in staat te stellen om een eigen waardering op te bouwen. Het maken van deze representatie is niet neutraal: enerzijds kijken wij als auteurs onvermijdelijk met een architecturale bril naar deze gebouwen, anderzijds is dit werk de vertaling van een opgebouwd inzicht dat in hoofdzaak gestoeld is op gesprekken met bewoners. Het is verleidelijk van buitenaf over deze woongebouwen een oordeel te vellen, maar niemand vat de werking en geest van deze gebouwen beter dan de bewoners zelf.

Behind the permanence of facades, an internal metabolism generates a life of forms that is correlated to the diversity of forms of life. … Once construction is complete, it seems that buildings no longer open their doors.4

Het wandelen langs en fotograferen van deze gebouwen, met het coverbeeld van deze masterproef als exponent, leidde al snel tot een nieuwsgierigheid naar wat zich achter de façades afspeelde. Geïnspireerd door de Belgische bijdrage aan de 14de architectuurbiënnale van Venetië, gepubliceerd in het boek Interieurs: notes et figures, startte onze zoektocht naar interieurs en gesprekken met bewoners. We verspreidden fysieke kaartjes en lanceerden een digitale enquête, die uiteindelijk de basis zou vormen voor deze masterproef. In die korte vragenlijst peilden we onder meer naar de appreciatie die de bewoners voor hun appartement koesteren. Dat het gemiddelde antwoord voor de beoordeling van het uiterlijk van hun gebouw 2,8 op een schaal van 5 bedroeg terwijl het interieur gemiddeld een score van 4,2 kreeg, wakkerde onze nieuwsgierigheid alleen maar verder aan. In een latere fase belden we ook onverwacht aan bij een vijftiental appartementen, wat uiteindelijk resulteerde in een totaal van zo’n 35 bezoeken.

Uit het merendeel van deze bezoeken kwamen opvallend gelijkaardige conclusies naar voren. Vrijwel alle bewoners gaven aan graag in hun appartement te wonen, weinigen zouden het willen inruilen voor een nieuwbouwappartement elders. De onbedoelde overmaat die in veel plannen vervat zit, zorgt voor een aangenaam gevoel van ruimte. Door het beperkte verliesoppervlak gaven veel bewoners bovendien aan dat ze tijdens de winter nauwelijks moeten verwarmen. Tegelijk wordt in bijna elk gebouw een gemis aan fietsstalling ervaren, het gevolg van de focus op de auto in de bouwperiode. Ook liftkokers voldoen zelden aan de hedendaagse normen, ze zijn vaak te klein en blijken bovendien moeilijk toegankelijk, doordat ze dikwijls achter enkele traptreden liggen.

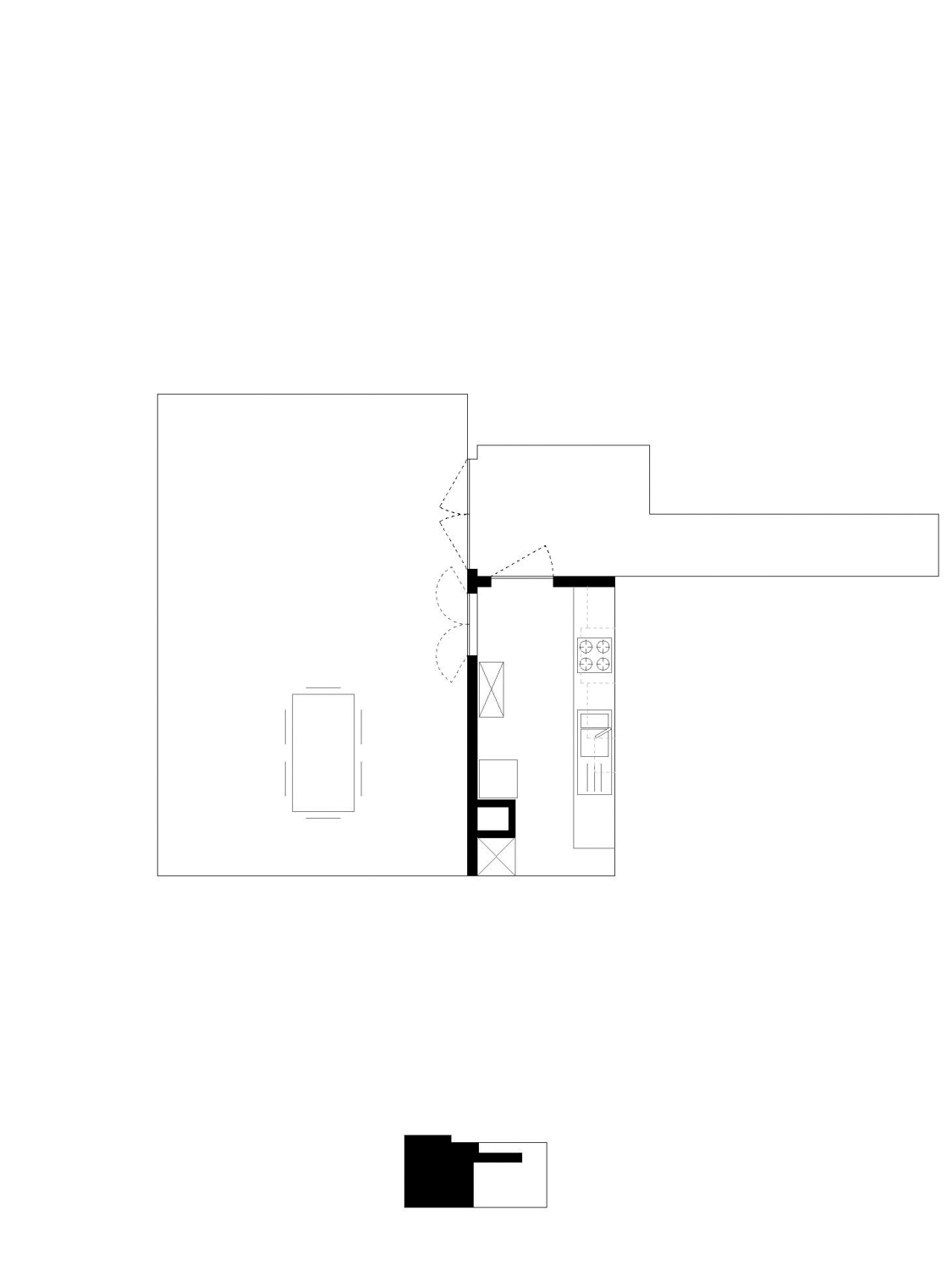

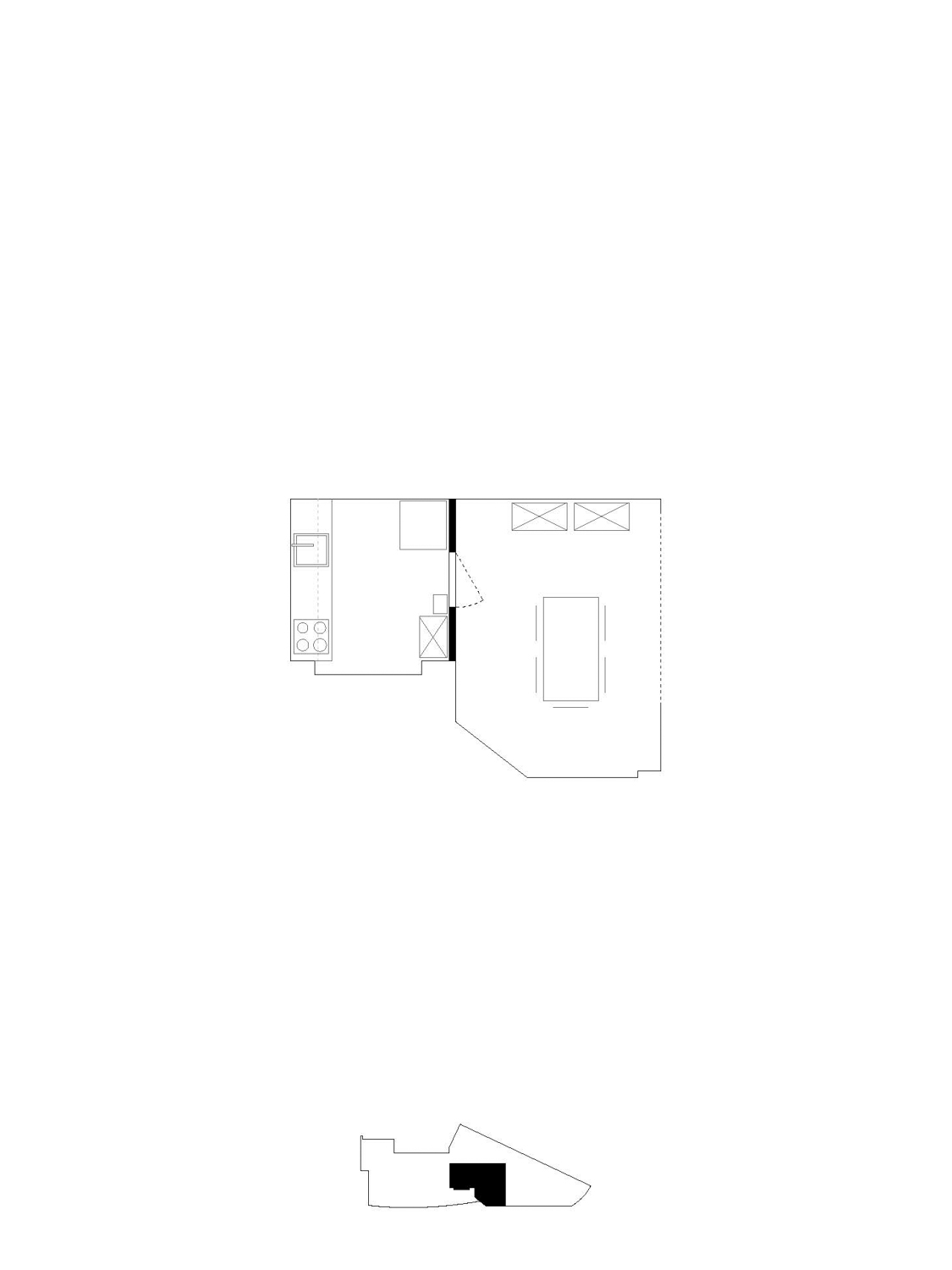

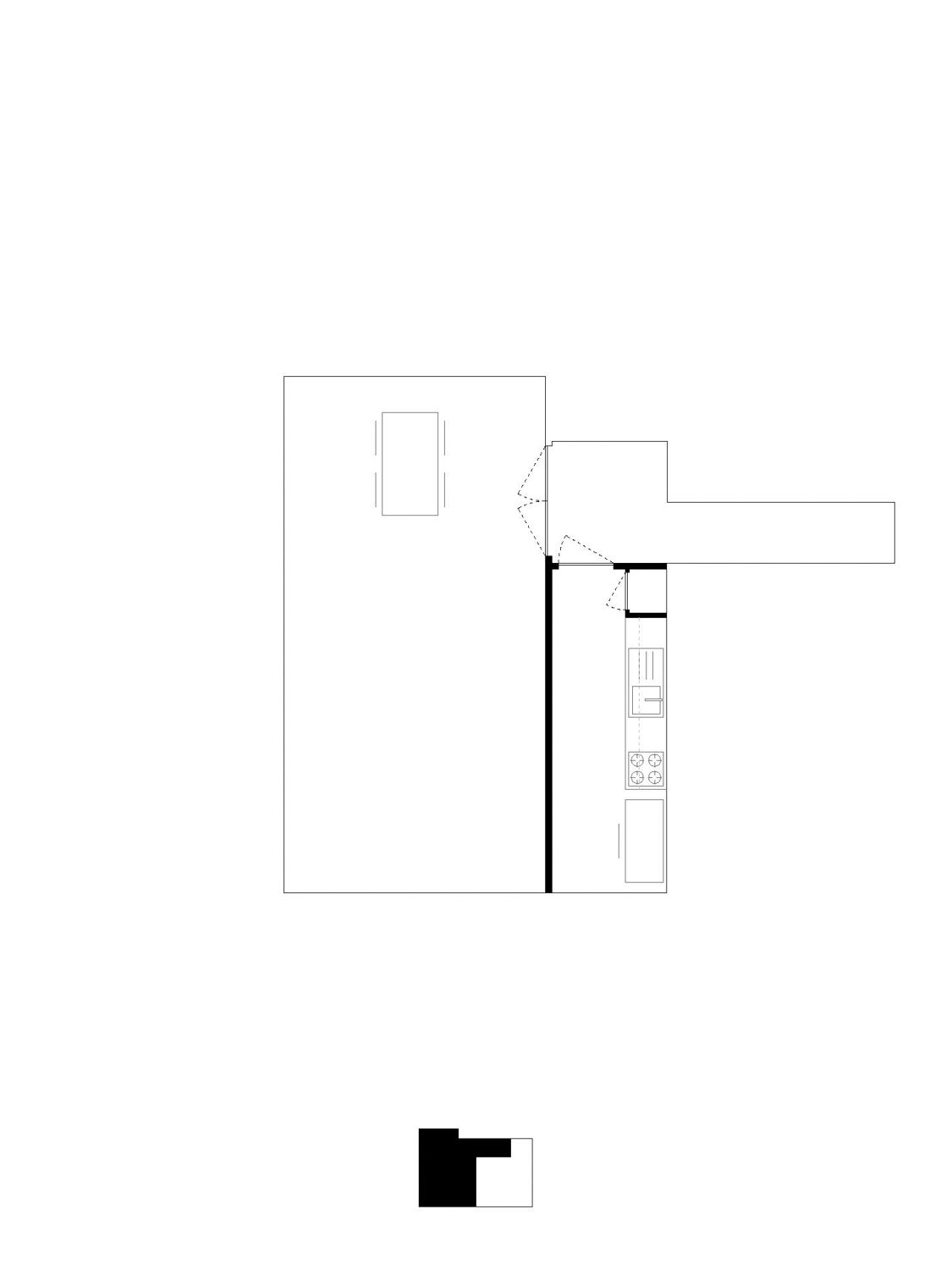

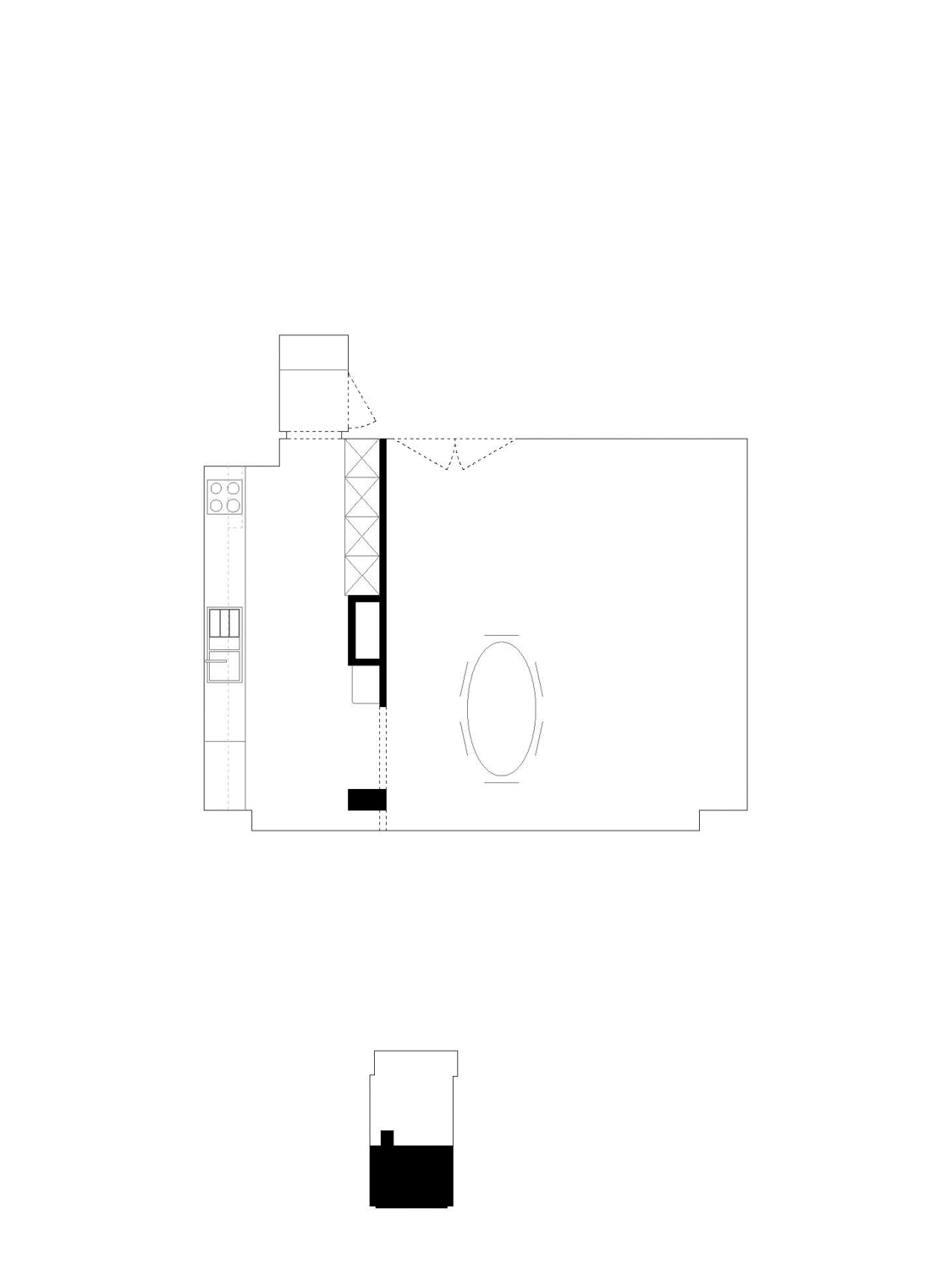

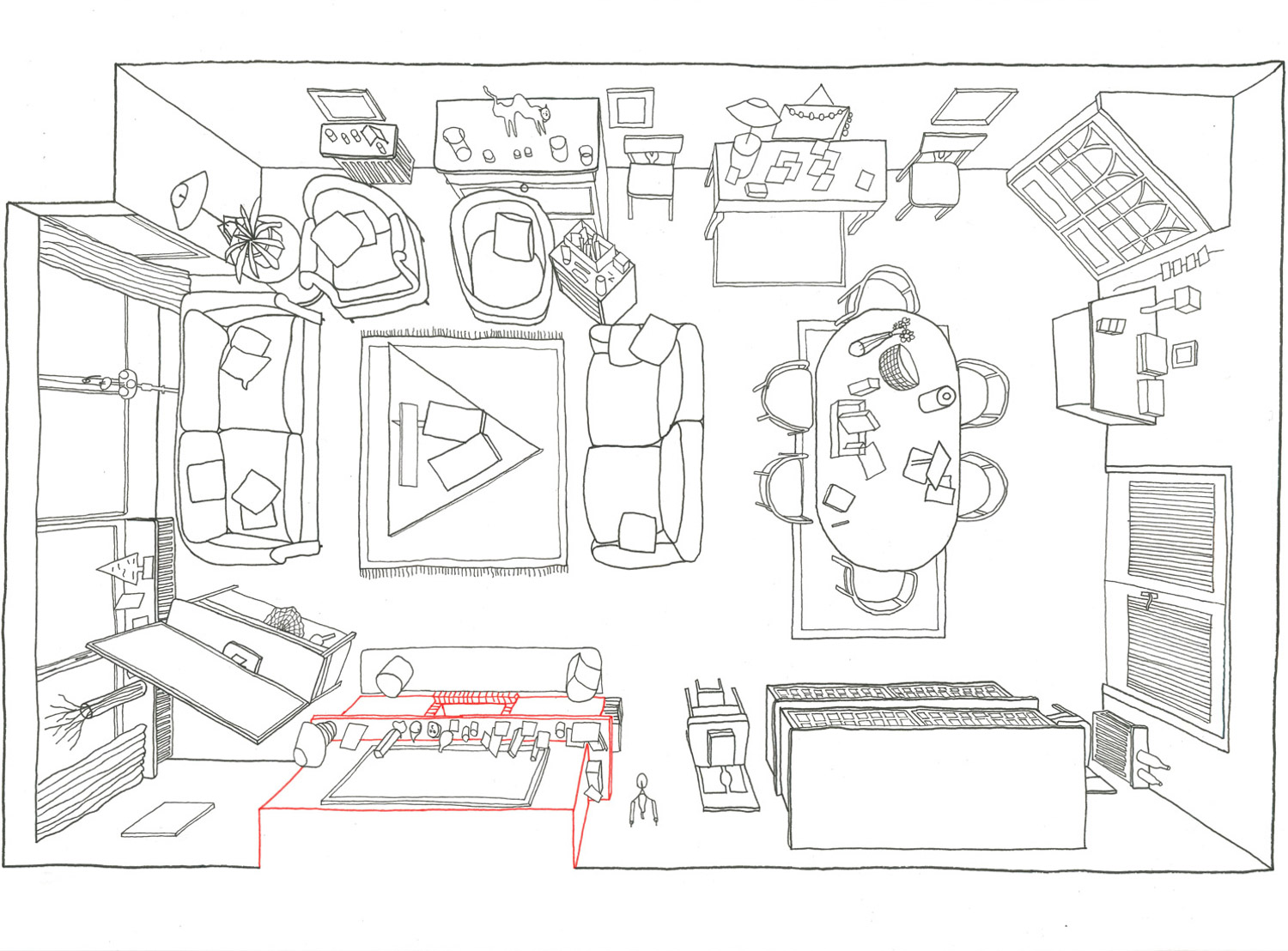

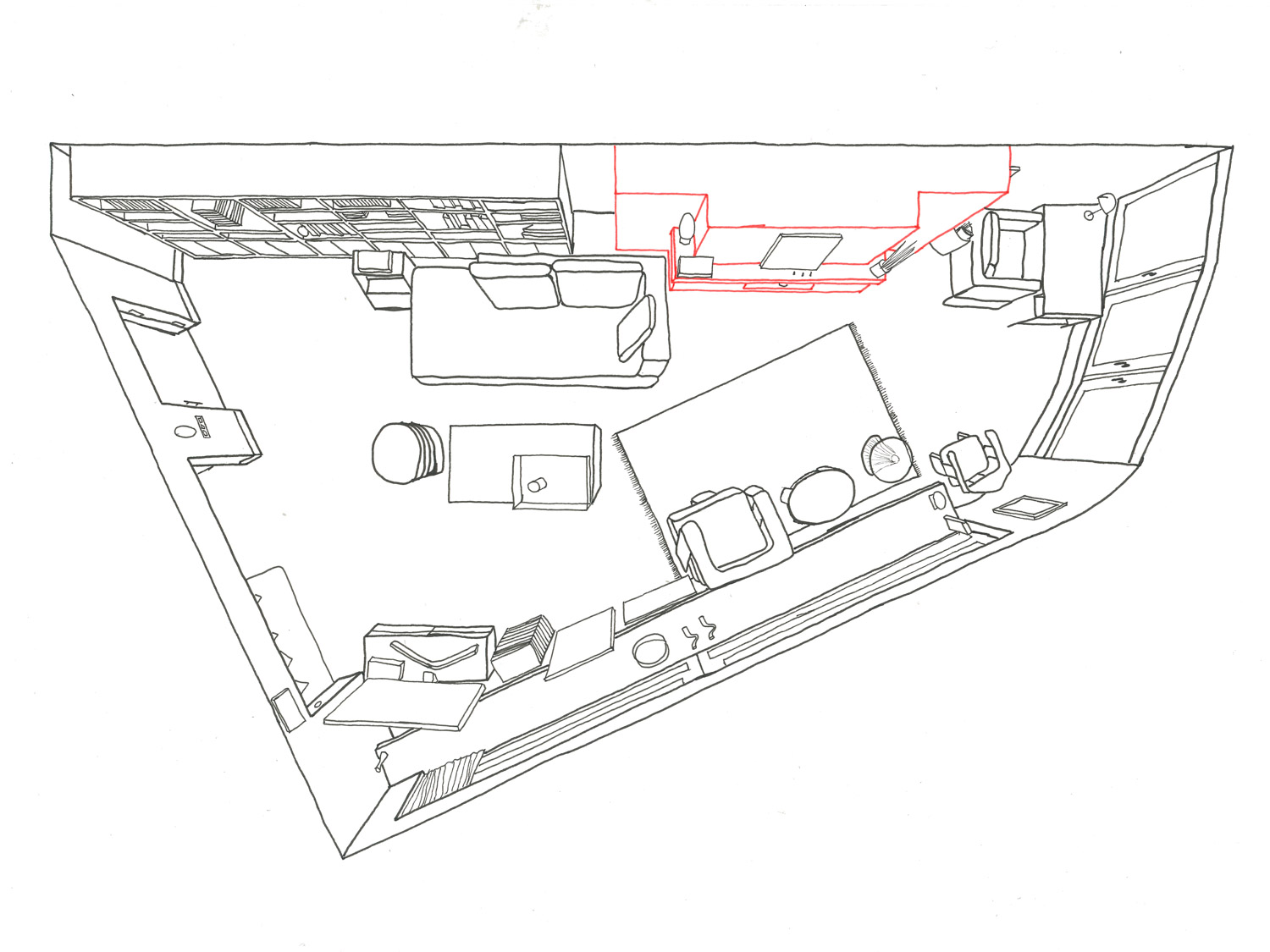

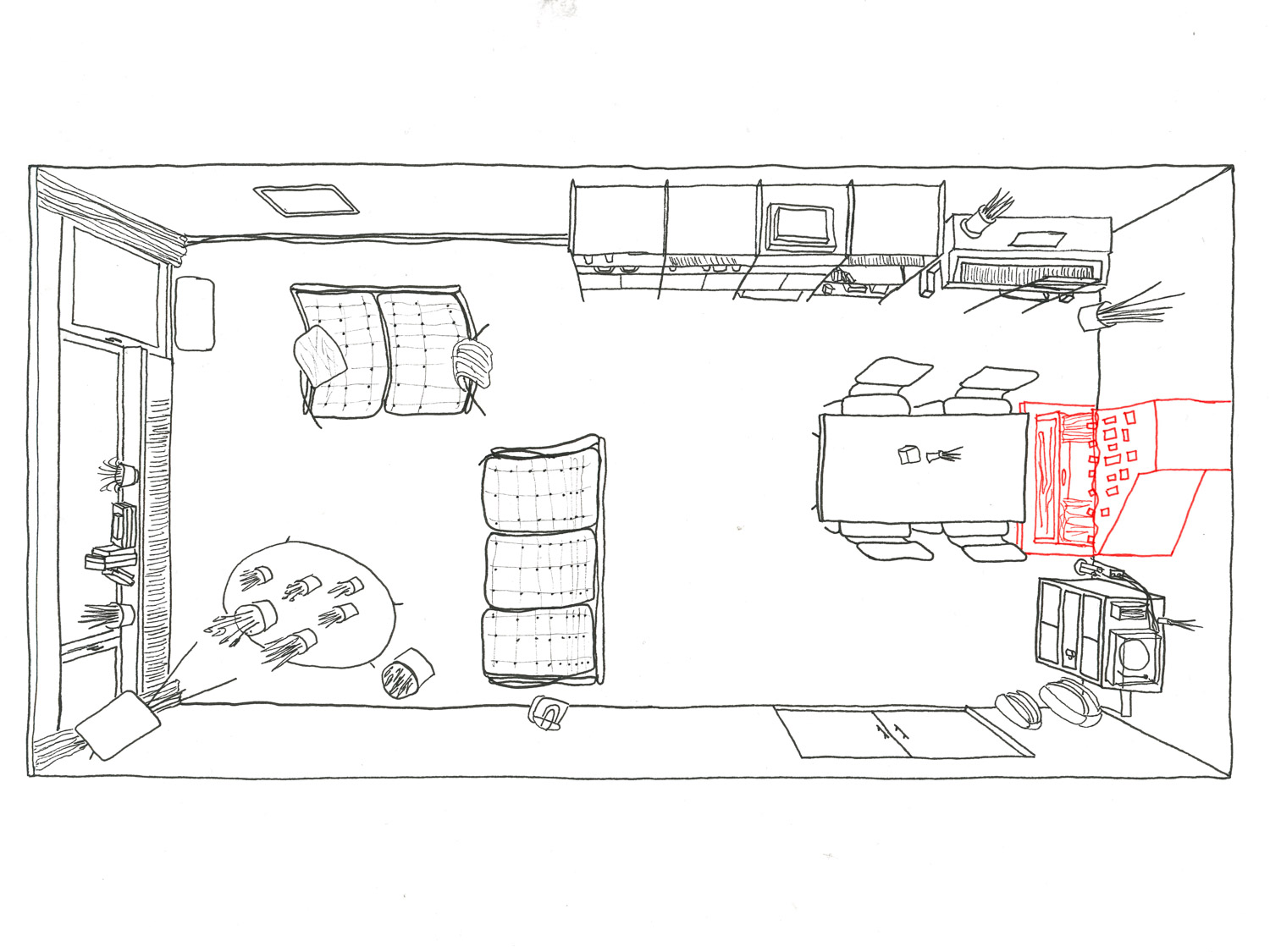

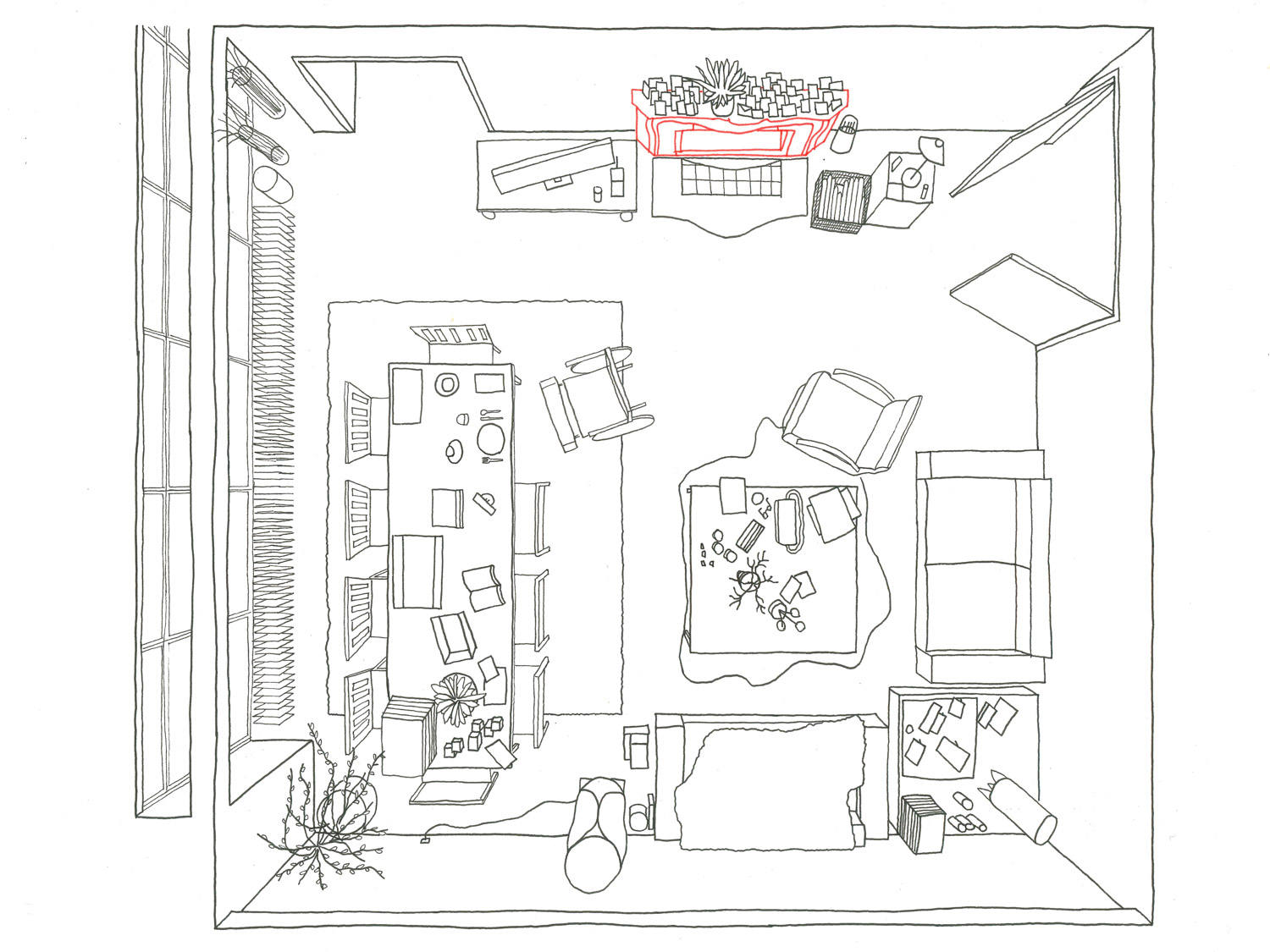

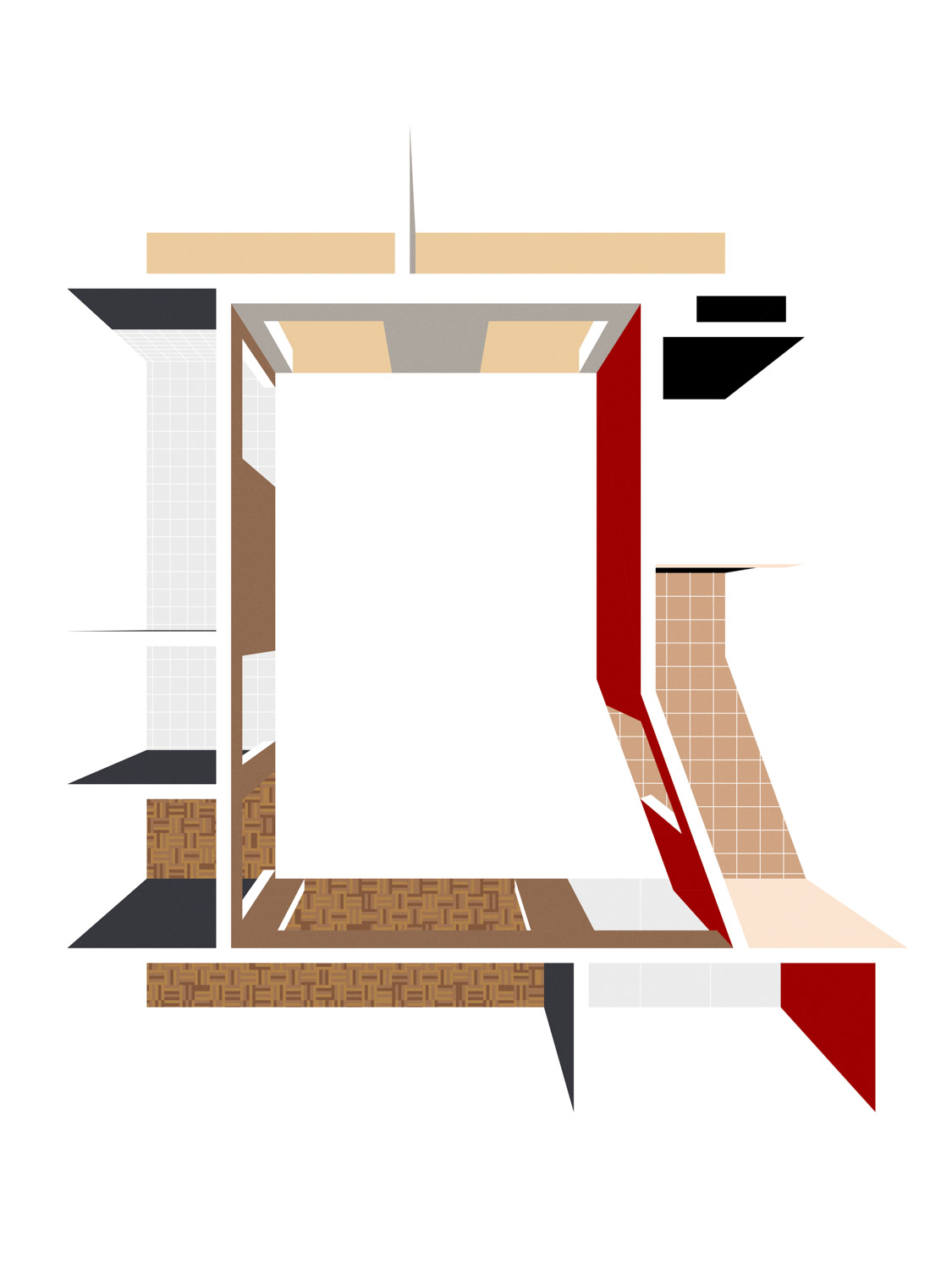

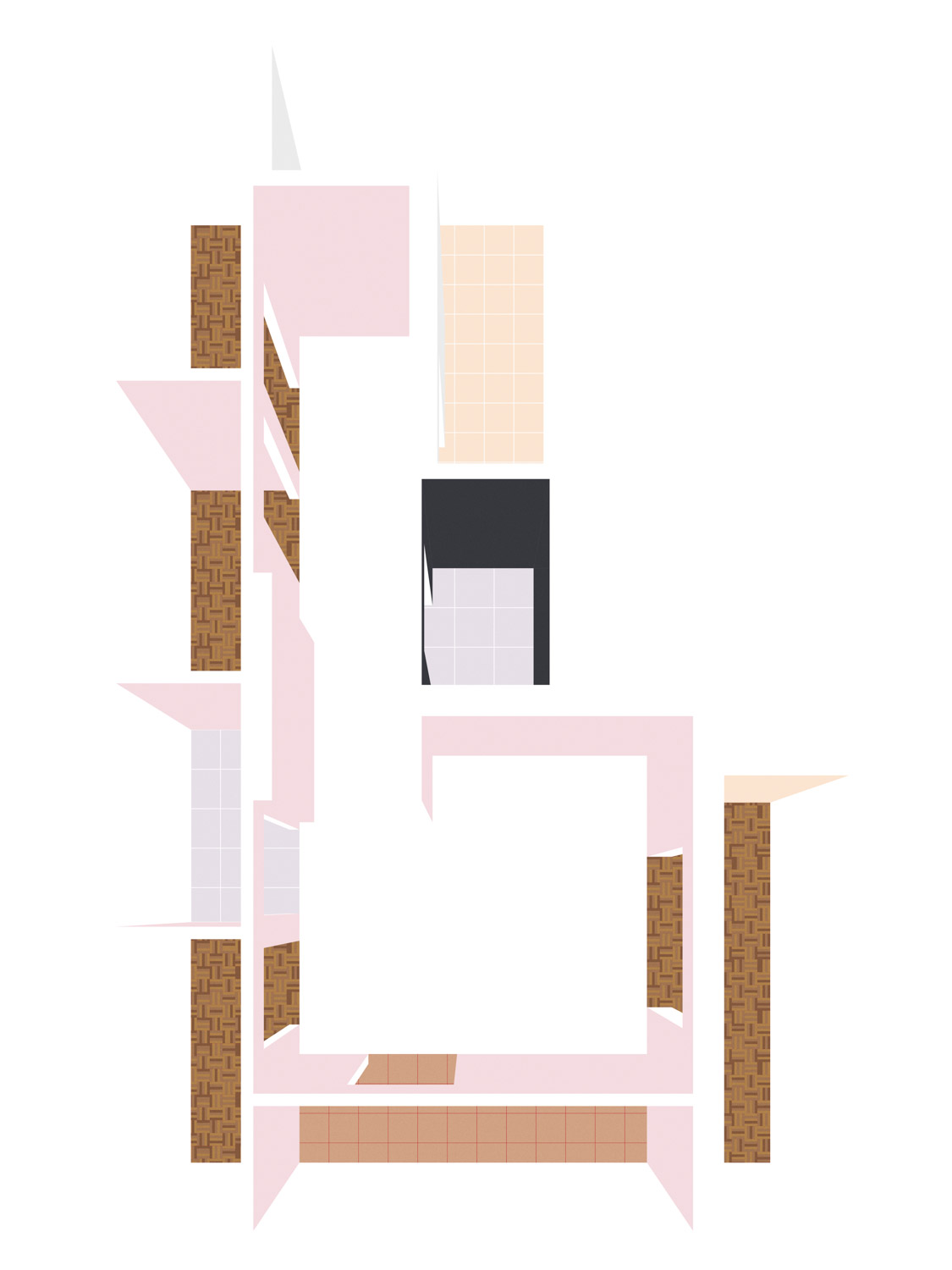

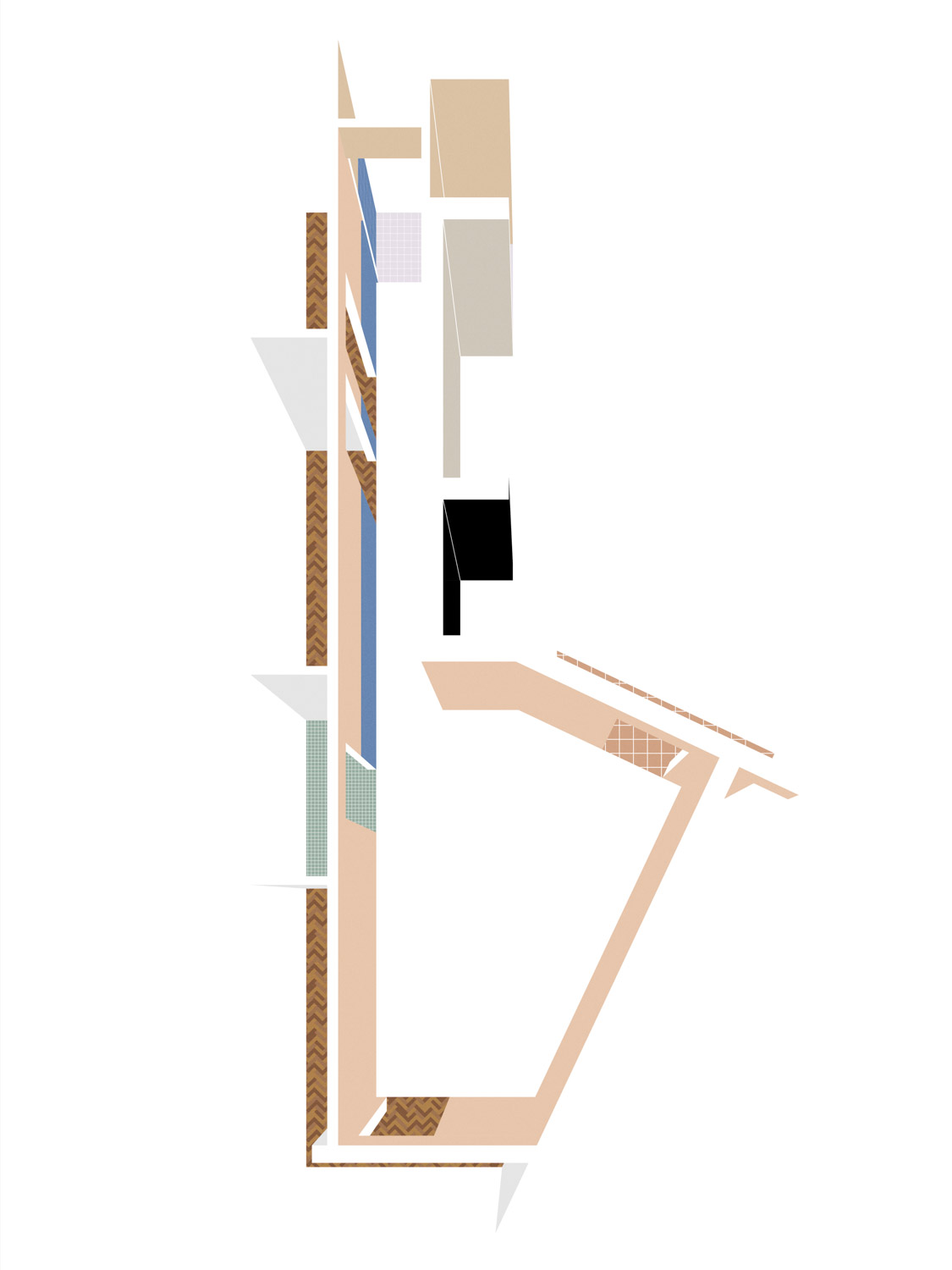

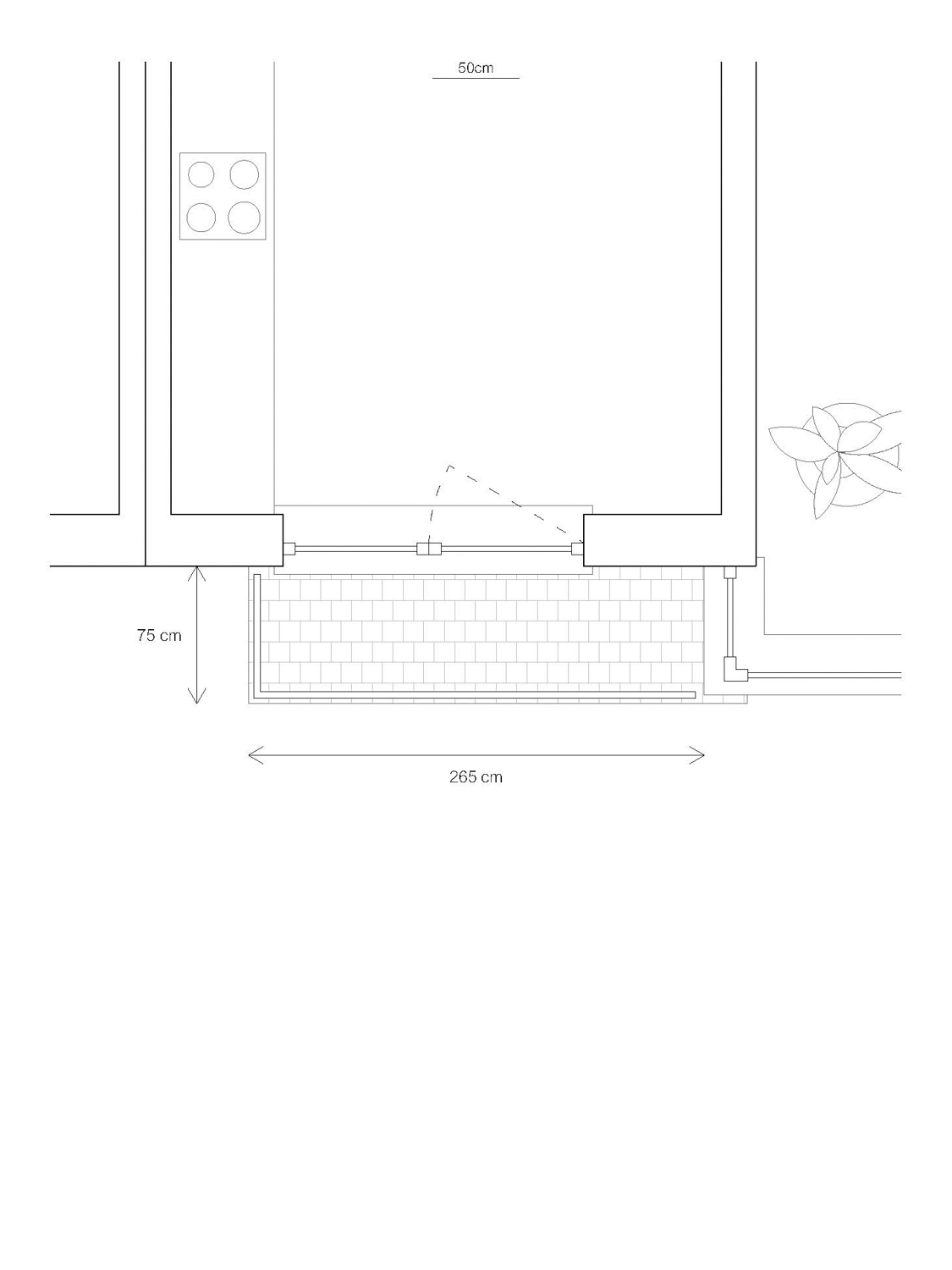

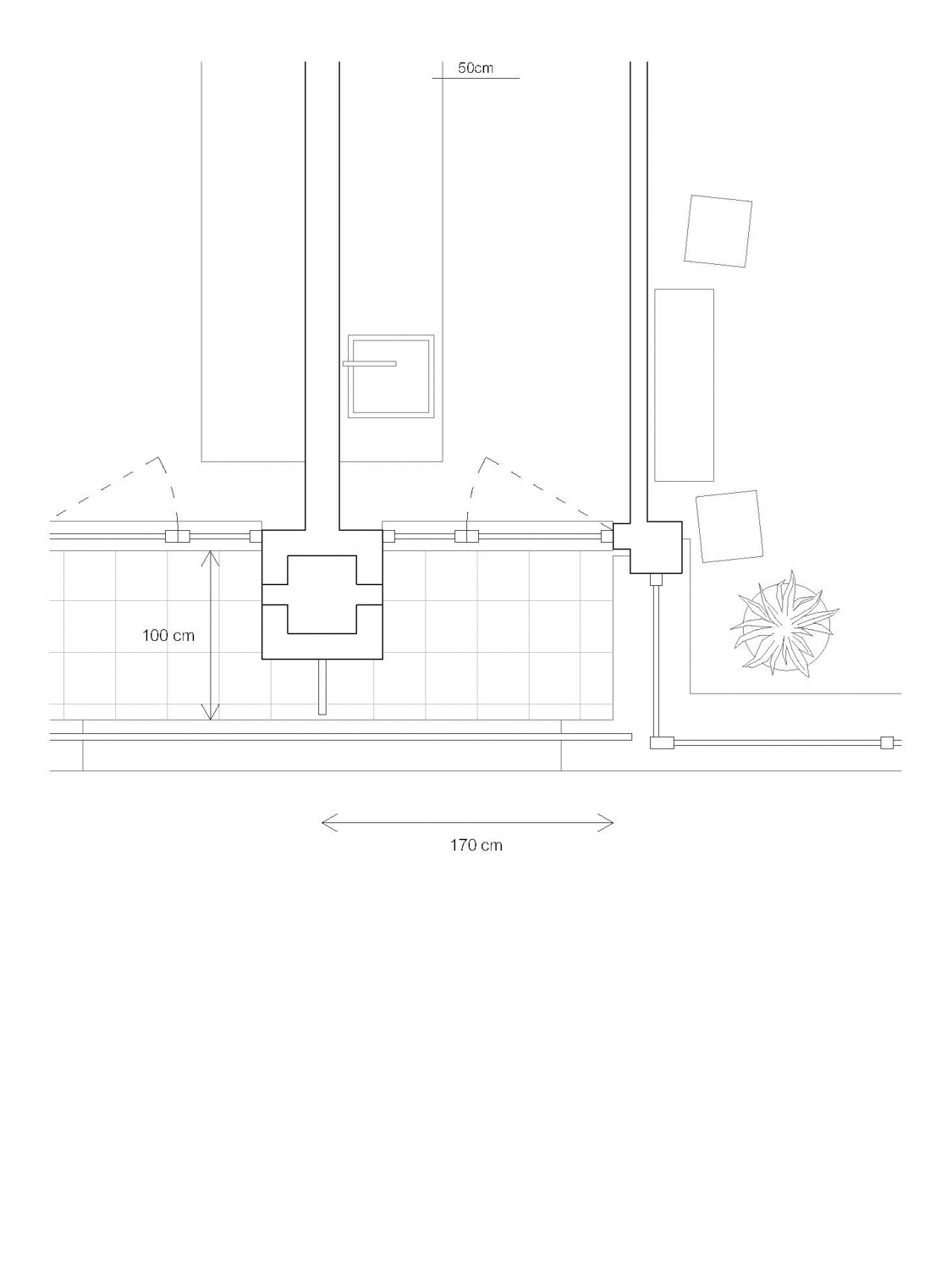

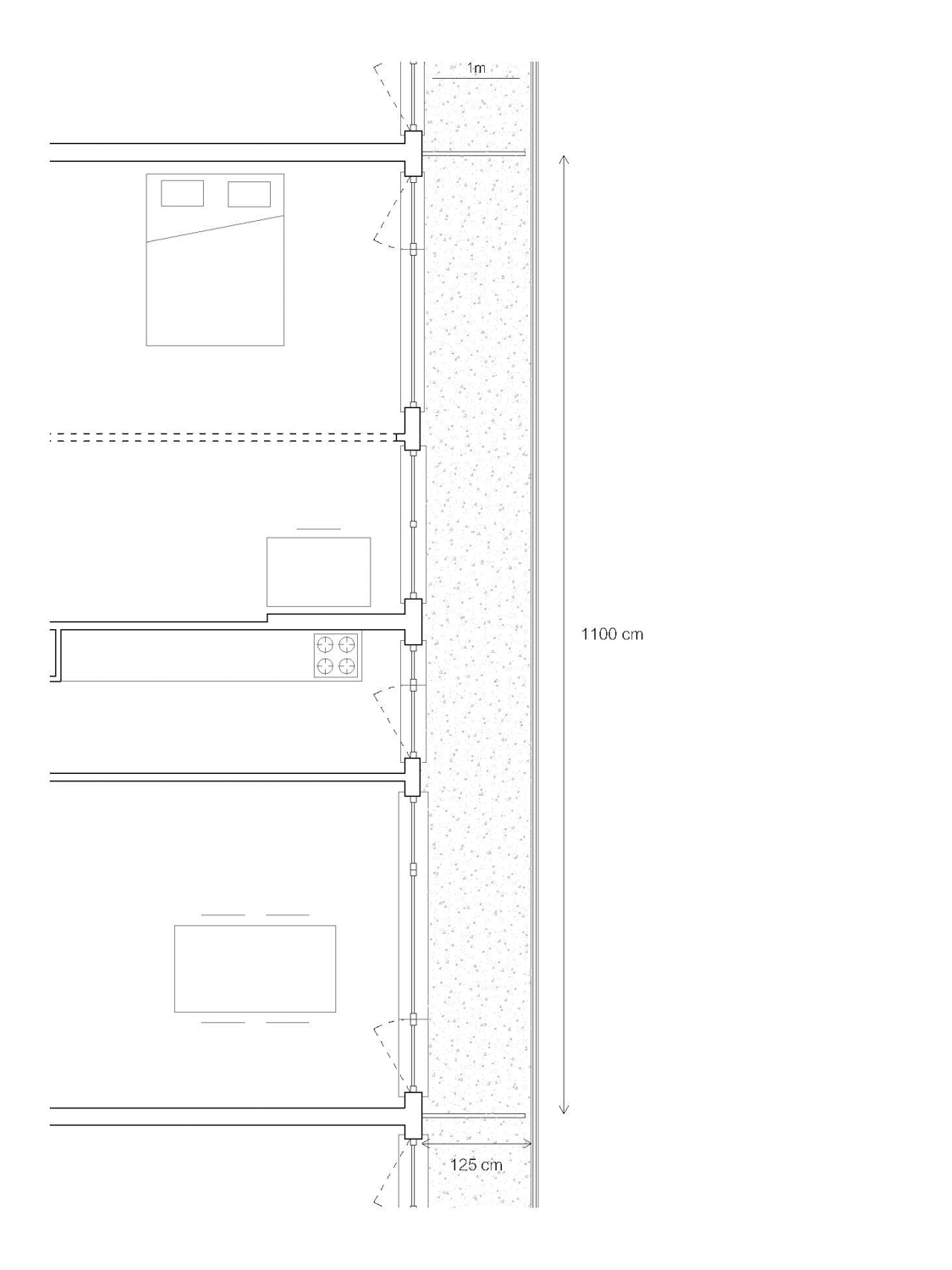

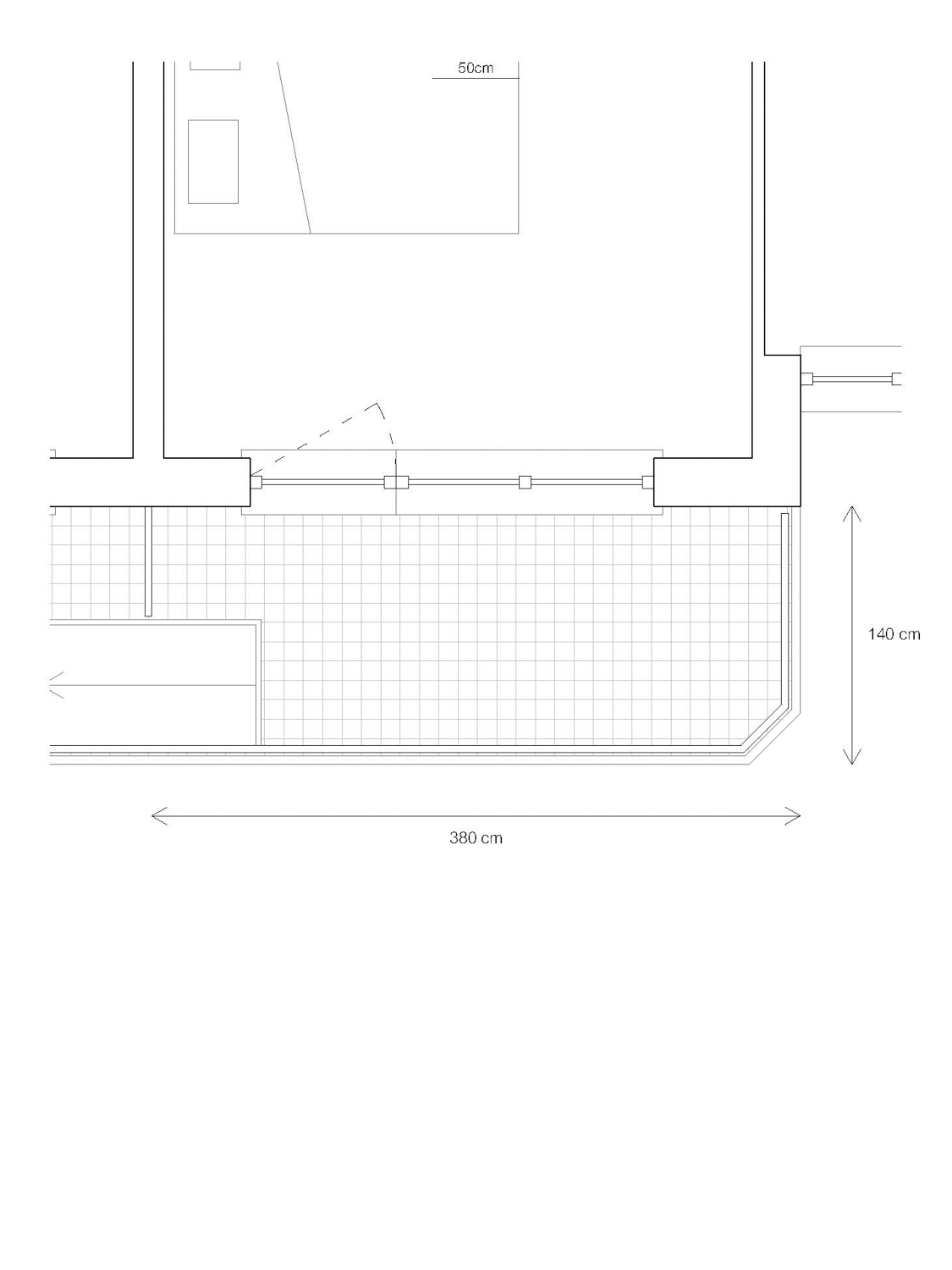

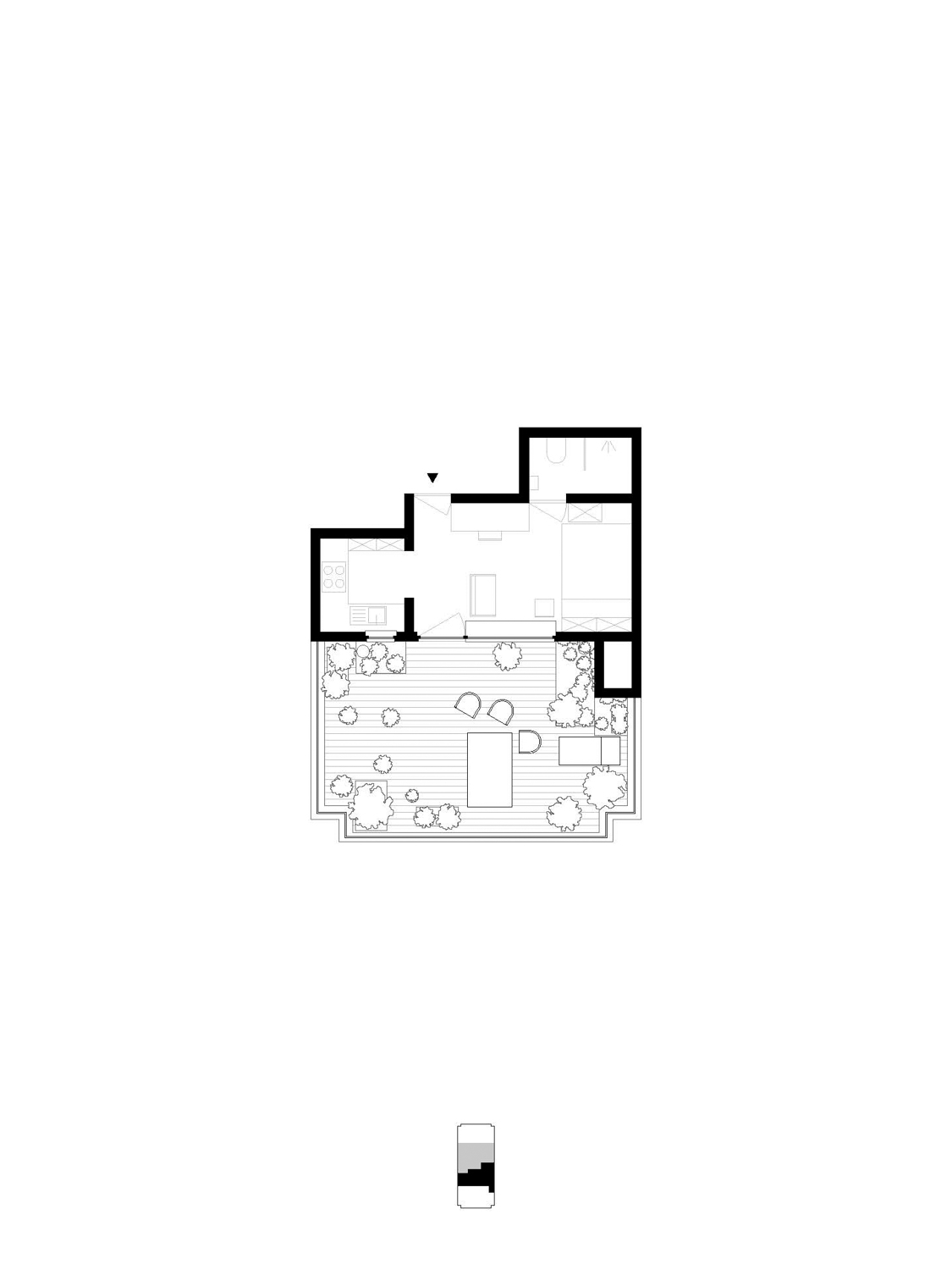

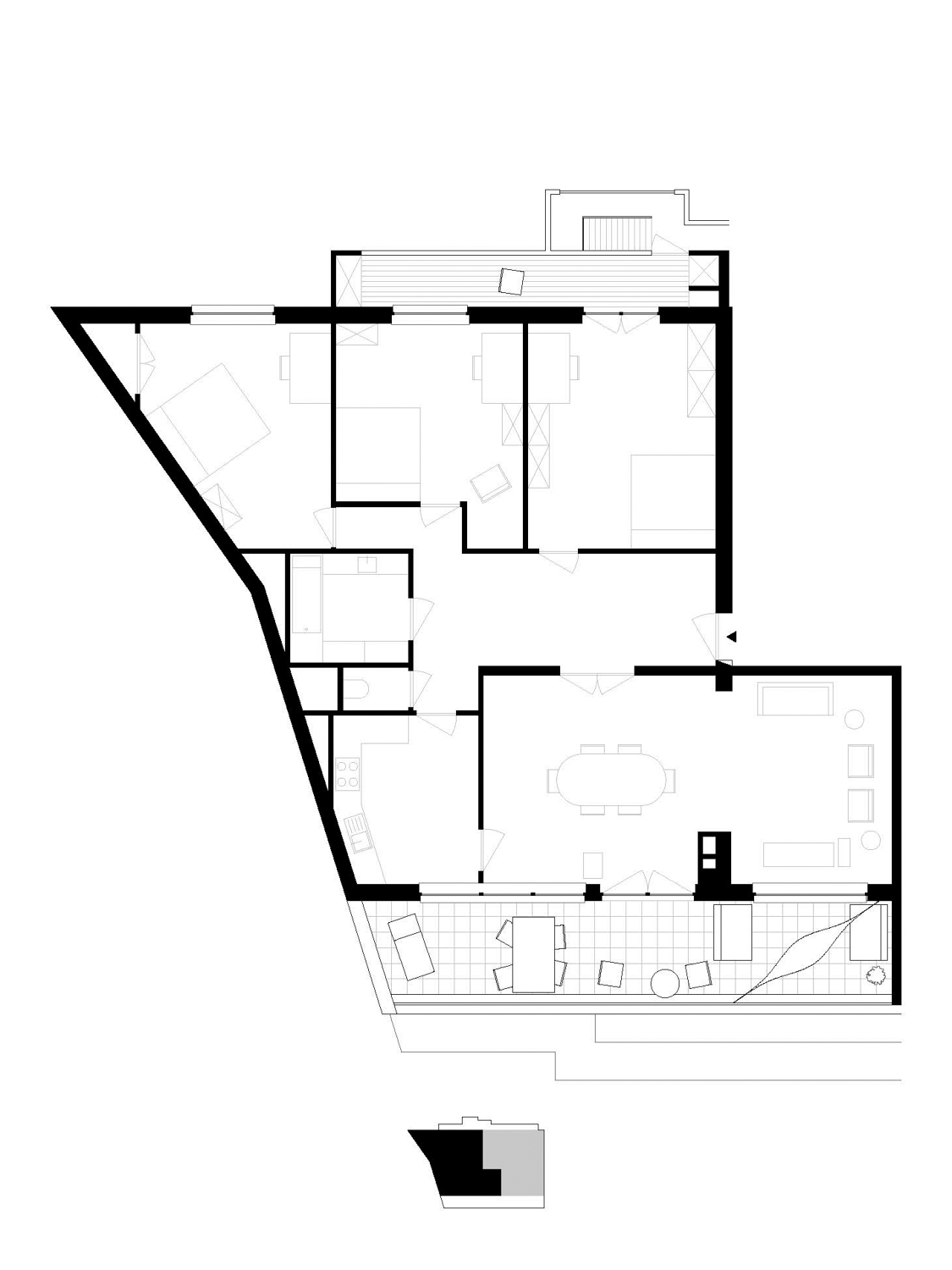

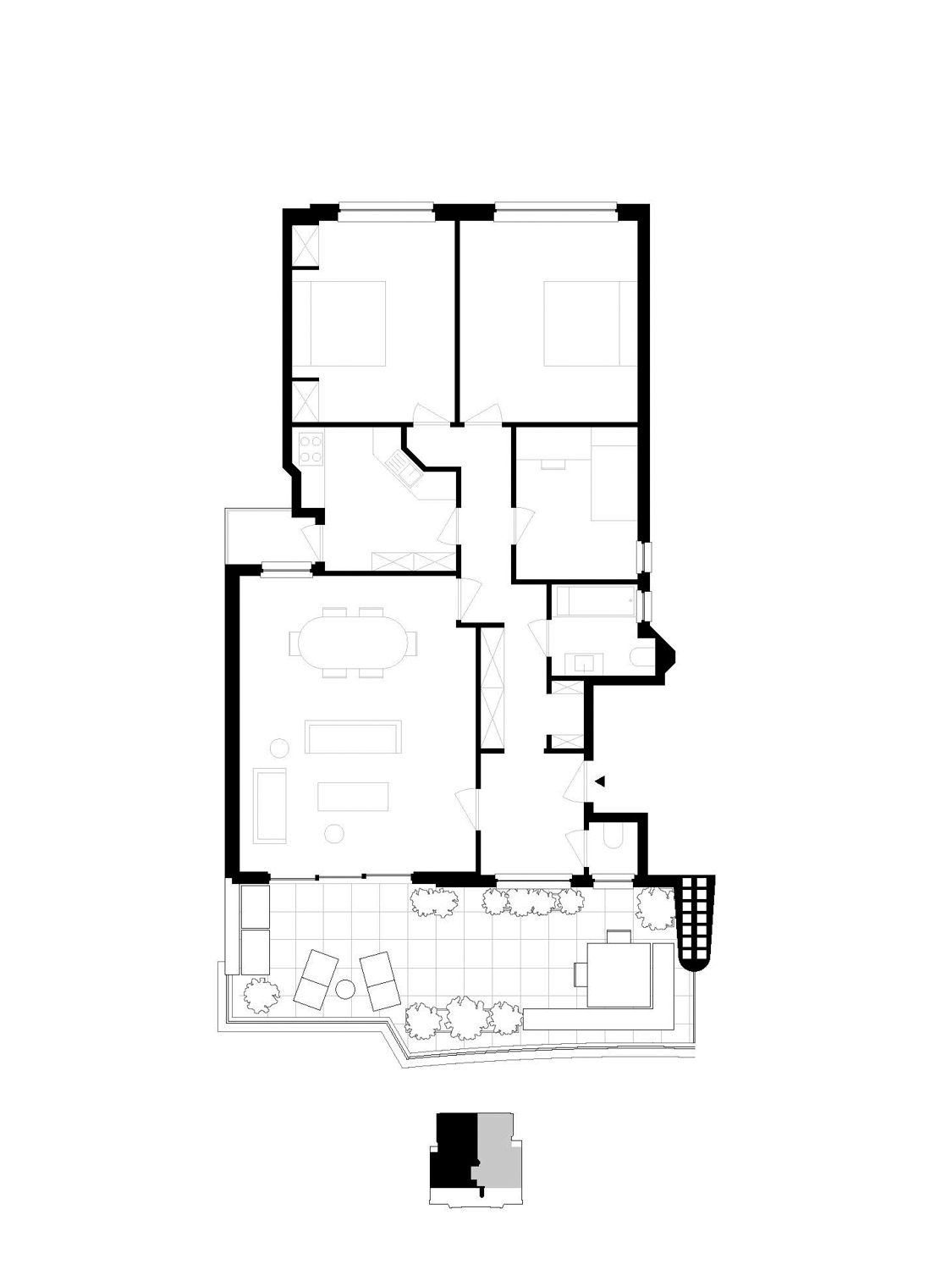

De masterproef bespreekt elf fenomenen die typerend zijn voor de architectuur van deze onzichtbare reuzen. Elk fenomeen wordt ingeleid door een kaderende tekst die, waar mogelijk en relevant, het fenomeen ook van een beknopte historische context voorziet. Vervolgens wordt elk fenomeen geïllustreerd aan de hand van vier à vijf cases, die telkens eerst kort worden ingeleid. Bij elke case hoort een tekening die het fenomeen probeert te vatten en zichtbaar te maken. De tekenstijl verschilt per hoofdstuk en is afgestemd op het karakter van het fenomeen. Na de tekening volgen twee foto’s die tonen hoe het fenomeen zich in de realiteit manifesteert – binnen of buiten het appartement. De focus ligt bij deze cases niet per se op een exacte opmeting van de bestaande toestand, maar op het ontwikkelen van een grafiek die het sentiment rond het fenomeen visueel probeert te vatten.

In Ghent, and by extension in almost all Belgian cities, an arsenal of collective housing buildings from the 1960s and 1970s helps shape the urban landscape. Scattered throughout the city, often along major thoroughfares or near park areas, this mid-rise housing distinctly stands apart from its surroundings. Prominent and omnipresent, yet until now largely ignored. As city dwellers, we often remain blind to these invisible giants: unconsciously, our focus turns to the ‘beautiful historical city,’ allowing this more recent architectural production only into the periphery of our gaze. When these housing blocks are spoken or written about, they are quickly dismissed as ugly, banal, characterless, or disruptive to scale. And yet, these buildings are still very much inhabited, appear cherished by their residents, and are in demand on the real estate market. It is within this tension that the research of this thesis unfolds.

To understand the origins of these developments, we must return to 1962. In the aftermath of the Second World War, Belgium experienced a rapidly growing housing shortage. Cities were confronted with an increasing demand for dwellings. At the same time, the economic climate of the 1960s—characterized by rising interest rates and cautious public investment in housing—provided ever more opportunities for the private market. Private developers, Amelinckx and Etrimo foremost among them, were then granted the possibility to provide housing for the broad middle class themselves and to push through their development model1, which led to densification and expansion of the urban fabric2. Crucial here was the “Act of March 29, 1962 concerning the organization of spatial planning and urbanism,” which introduced new instruments and placed the responsibility for spatial planning in the hands of the government. This marked an important turning point for a country that had previously lacked a clear planning tradition.

The use of “bijzondere plannen van aanleg” (special development plans, BPA’s), which allowed local authorities to determine the use and design of portions of their territory, increased sharply during this period. The BPA’s created at the time often permitted greater building heights than previously customary and thus made the development of this mid-rise housing possible.

In parts of Ghent where no BPA’s were available, building permits were assessed by the college of mayor and aldermen. Building regulations open to interpretation, the political appeal of modern urban development with which politicians of that era liked to associate themselves, and pressure from the private real estate sector brought forth a stream of exceptions. Ironically, this modern typology thus found its implantation primarily in a city model despised by the very founders of modernism.

In the 1980s, a policy reversal, stemming from a renewed focus on the historical city, brought this architectural production to a halt. BPA’s were revised, and an extensive inventory of heritage sites made further development of such buildings virtually impossible. The result is an urban landscape that, to this day, is characterized by an enigmatic mix of collective high-rise and more traditional architecture that remains closer to the ground.

Today, we find ourselves at a turning point. These invisible giants, which once embodied the progressive thinking of their time, are now 50 years old or more and are approaching the end of their lifespan. They stem from another era and another vision of insulation, technology, and comfort. This makes them highly vulnerable in their architectural appearance today: sustainability operations almost invariably seem to result in a contemporary anonymous in-between language.

Moreover, these buildings constitute a substantial part of Ghent’s housing stock. Attaching an exact number is difficult, but a comprehensive catalogue compiled earlier shows that more than five hundred of these buildings are located in Ghent3. A generic architectural language that strips these buildings of all individuality threatens to spread throughout the city in the coming years, while at the same time this typology lacks a nuanced and in-depth debate that transcends norms and figures.

By looking at these buildings in a new way, this thesis seeks to serve as a starting point for such a debate. It investigates the contemporary relevance of this typology, offers the reader observations, points to qualities and shortcomings, and above all seeks to enable the reader to develop their own appreciation. The making of this representation is not neutral: on the one hand, as authors we inevitably look at these buildings through an architectural lens; on the other hand, this work is the translation of an insight built up primarily from conversations with residents. It is tempting to judge these housing buildings from the outside, but no one captures their functioning and spirit better than the residents themselves.

Behind the permanence of facades, an internal metabolism generates a life of forms that is correlated to the diversity of forms of life. … Once construction is complete, it seems that buildings no longer open their doors.4

Walking along and photographing these buildings, with the cover image of this thesis as a key example, quickly sparked curiosity about what was happening behind the façades. Inspired by the Belgian contribution to the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale, published in the book Interieurs: notes et figures, we began our search for interiors and conversations with residents. We distributed physical postcards and launched a digital survey, which would eventually form the basis of this thesis. In that short questionnaire, we asked, among other things, about the appreciation residents had for their apartment. The fact that the average score for the exterior of their building was 2.8 on a scale of 5, while the interior received an average score of 4.2, only fueled our curiosity further. In a later phase, we also rang the doorbells of about fifteen apartments unannounced, which ultimately resulted in a total of roughly 35 visits.

From the majority of these visits, strikingly similar conclusions emerged. Virtually all residents indicated that they enjoyed living in their apartment; few would want to exchange it for a new-build apartment elsewhere. The unintended generosity embedded in many floor plans provides a pleasant sense of space. Due to the limited loss of surface area, many residents also indicated that they hardly needed to heat during winter. At the same time, almost every building suffers from a lack of bicycle storage, a consequence of the car-focused mentality of the construction period. Elevator shafts also rarely meet contemporary standards; they are often too small and prove difficult to access, as they are frequently located behind a few steps.

The thesis discusses eleven phenomena typical of the architecture of these invisible giants. Each phenomenon is introduced by a framing text that, where possible and relevant, also provides a concise historical context. Each phenomenon is then illustrated through four to five cases, each briefly introduced. Every case includes a drawing that attempts to capture and visualize the phenomenon. The drawing style differs per chapter and is attuned to the character of the phenomenon. Following the drawing are two photographs showing how the phenomenon manifests in reality—inside or outside the apartment. The focus in these cases lies not so much on exact measurements of the existing condition, but on developing a graphic that visually captures the sentiment surrounding the phenomenon.

De elf fenomenen die in deze masterproef zijn belicht, vormen geen sluitend beeld van de typologie. Ze willen deze architectuur niet verheerlijken. Ze maken ruimte: voor nuance, voor twijfel, voor onverwachte schoonheid. Ze tonen hoe deze gebouwen tegelijk tekortschieten en verrassen. Hoe kwaliteiten ontstaan, vaak onbedoeld, en hoe broos ze zijn. Ze vertrekken vanuit het gebouwde, het bestaande, niet uit nostalgie, maar vanuit het besef dat er een einde moet komen aan de eindeloze consumptie van ruimte en materiaal. Ze tonen hoe tekenen, kijken, fotograferen en spreken ook vormen van onderzoek kunnen zijn - niet om exact vast te leggen of af te meten, maar om te begrijpen. Ze spannen een boog tussen het lelijke en het geliefde, het banale en het fascinerende. Ze hebben ons, de auteurs, geholpen anders te kijken naar deze gebouwen en de stad.

Tegelijk werpt deze herlezing een verontruste blik vooruit. Veel van deze gebouwen zijn intussen vijftig jaar of ouder, en hun toekomst is onzeker. Renovaties dringen zich op, maar verlopen vaak zonder inzicht in of respect voor wat er is. Een natuurstenen vensterdorpel met een levensduur van meer dan een eeuw wordt zonder aarzeling vervangen door een spaanplaat die hooguit vijftien jaar meegaat. Mede-eigenaarschap maakt collectief en kwalitatief onderhoud moeilijk. De bewoners - in vele gevallen de grootste pleitbezorgers van hun gebouw - dreigen, vaak onbedoeld, bij te dragen aan de ontmanteling ervan. Beleidsmatig ontbreekt een helder kader: begeleiding en stimulansen blijven beperkt tot wie de middelen heeft, terwijl het grootste deel van het patrimonium buiten beeld blijft. Wat ontbreekt is een toekomstvisie die verder kijkt dan normen en cijfers. Een visie die woonkwaliteit, materialiteit en collectief eigenaarschap durft herdenken.

Deze masterproef pretendeert geen sluitende antwoorden te bieden. Ze wil vooral bijdragen aan het gesprek. De fenomenen, beelden en stemmen van bewoners vormen samen een aanzet, een pleidooi om opnieuw te kijken - en om dat kijken om te zetten in zorgzaam handelen.

The eleven phenomena highlighted in this thesis do not provide a complete picture of the typology. They do not aim to glorify this architecture. They create space: for nuance, for doubt, for unexpected beauty. They show how these buildings simultaneously fall short and surprise. How qualities emerge, often unintentionally, and how fragile they are. They start from what exists, from the built environment, not from nostalgia, but from the awareness that the endless consumption of space and materials must come to an end. They demonstrate how drawing, observing, photographing, and speaking can also be forms of research — not to record or measure exactly, but to understand. They span a spectrum between the ugly and the beloved, the banal and the fascinating. They have helped us, the authors, to see these buildings and the city differently.

At the same time, this rereading casts a concerned eye forward. Many of these buildings are now fifty years or older, and their future is uncertain. Renovations are necessary but often proceed without understanding or respect for what exists. A natural stone window sill with a lifespan of over a century is replaced without hesitation by chipboard that lasts at most fifteen years. Co-ownership complicates collective and qualitative maintenance. The residents — often the strongest advocates for their building — may, often unintentionally, contribute to its dismantling. Policy-wise, a clear framework is lacking: guidance and incentives remain limited to those with resources, while the majority of the patrimony remains invisible. What is missing is a vision for the future that goes beyond norms and numbers — a vision that dares to rethink living quality, materiality, and collective ownership.

This thesis does not claim to offer definitive answers. Its main aim is to contribute to the conversation. The phenomena, images, and voices of residents together form an initial step, a plea to look again — and to translate that looking into careful action.